From his apartment in Manila's Bonifacio Global City, Eric Go can still see planes going past his windows. Like many in Southeast Asia's middle class, Go, who grew up in the U.S. and works for an e-commerce company, has been used to near-seamless mobility: ride-hailing, low-cost airlines and direct flights back to his family in New York.

"It was never really an issue. I can hop on a plane and go wherever I want to go. That's how I see freedom," he said. "It's like, OK, there's turmoil in Manila, or it gets too hot, I can leave. And now I can't leave at all."

Since the COVID-19 crisis intensified in mid-March, Go has been trying to get back to his parents in the U.S. But the few flights still running have become prohibitively expensive, and since most require long layovers, the risk of being stuck indefinitely in transit is high. All around the world, borders are slamming shut as governments try to contain a global pandemic that has already killed more than 40,000 people.

In the Asia Pacific, China, India, Singapore, Taiwan, Vietnam, New Zealand and Australia have all barred nonresidents from entering. Others, including Japan, have suspended visa waivers and imposed quarantines on most arrivals. Whole cities are on effective lockdown -- streets empty, businesses shuttered.

The suddenness with which these measures dropped into place is shocking for those who have only known an era of globalization and relative plenty. While Go's parents remember troops on the street in Manila and shortages in the shops, he has never experienced this level of uncertainty. "The normal amenities that you'd have in life have been stripped away. ... The question you ask is, how is it going to be next week? Will we still have bread next week? Will we still have eggs?" he said. "I have never experienced an egg shortage in my life. I've never had a curfew in my life."

A man walks through the Philippine capital of Manila, where President Rodrigo Duterte ordered a shutdown in mid-March. © Reuters

A man walks through the Philippine capital of Manila, where President Rodrigo Duterte ordered a shutdown in mid-March. © Reuters Even just a month ago, outside of a handful of countries, the daily disruptions were mundane. Businesspeople peered into phone screens on Zoom calls and Google Hangouts; spam folders were crammed with canceled invites to forums, seminars and news conferences that now feel like artifacts from another era.

Today, with the pandemic still out of control, a third of the global population is in some form of lockdown. Workforces have been atomized, schools closed, families scattered. Medical treatments are on hold. Weddings, graduations and reunions are delayed indefinitely. Sports events, from school tournaments to the Tokyo Olympic Games, have been postponed. Jobs lost. Businesses closed, possibly never to reopen. Deaths. Hundreds of thousands of individual traumas that add up to profound social, cultural, economic and political dislocations that will outlast the crisis.

"With the virus, the implications are huge. There are financial implications, there are social implications, there are health implications, there are implications on supply chains. Everything is impacted," said Sumit Agarwal, the Low Tuck Kwong distinguished professor of finance at the National University of Singapore. "People will have to think about new trade routes, new production capacity. ... We will have to rethink what borders are."

Lockdowns

On March 17, the Heritage Foundation, a U.S. think tank, declared Singapore the "freest economy" in the world. Less than a week later, the city-state all but sealed its borders. The Causeway, the road and rail bridge that links the island to Malaysia, was shut to the 400,000 people who cross every day for work. Nonresidents were banned even from transiting through Changi Airport, until this week one of Asia's busiest travel hubs. The national flag carrier, Singapore Airlines, cut 96% of its routes.

Singaporean graduate student David Tan caught one of the last flights out of the U.S., paying $1,000 to fly from his home in New Mexico via LAX.

"If I had stayed, I would have been relatively safe. But the longer I stayed, the harder it would have been to get out," he said, sounding remarkably cheerful over the phone on the first day of his government-mandated 14-day self-quarantine. "You're making all of these decisions in a short time frame. You don't have the time to plan everything. Everything is very spontaneous. It was an extremely stressful period."

The flight was full of airline staff in uniform being relocated back to Singapore, and U.S.-based Singaporeans making the calculation that they would rather wait out the pandemic at home -- close to their families, and where health care is more affordable, should the need arise.

At Singapore's Changi Airport, one of the largest transportation hubs in Asia, a baggage conveyor stands motionless behind unmanned check-in desks on March 30. © Reuters

At Singapore's Changi Airport, one of the largest transportation hubs in Asia, a baggage conveyor stands motionless behind unmanned check-in desks on March 30. © Reuters "If I fall ill in the U.S., even though I do have health insurance, a trip to the [emergency room] will set me back a significant chunk of money," Tan said. "Hospitalization would set me back a lot more. Put it this way: $1,000 to fly back to Singapore is really a saving."

Across the world, people have had to make these calculations, desperately trying to get themselves home and their families together. Hong Kong -- number two on the Heritage Foundation's list -- closed its land border with mainland China in February. From March 25, it also barred nonresidents from entering.

There, Shakib Pasha, who runs a group of restaurants and bars, was able to get his parents back into the city from Bangladesh before the lockdowns began -- although he still hasn't been able to see them, for fear of spreading the virus. "They travel back and forth. They were leaving things to the last minute, but we pushed them to come back," he said. "It was my sister's birthday yesterday, but I couldn't go. ... We're just avoiding each other as much as possible for the next two weeks."

Pasha's regular market research trips are on hold. A pop-up shop in Singapore he had planned for the first quarter of the year is now indefinitely postponed. In Hong Kong, he has had to cut back his business, alive to the reality that everyone making their way back to the city is a potential source of infection. "We're having to look at everything and ask -- is this safe to do now?" he said.

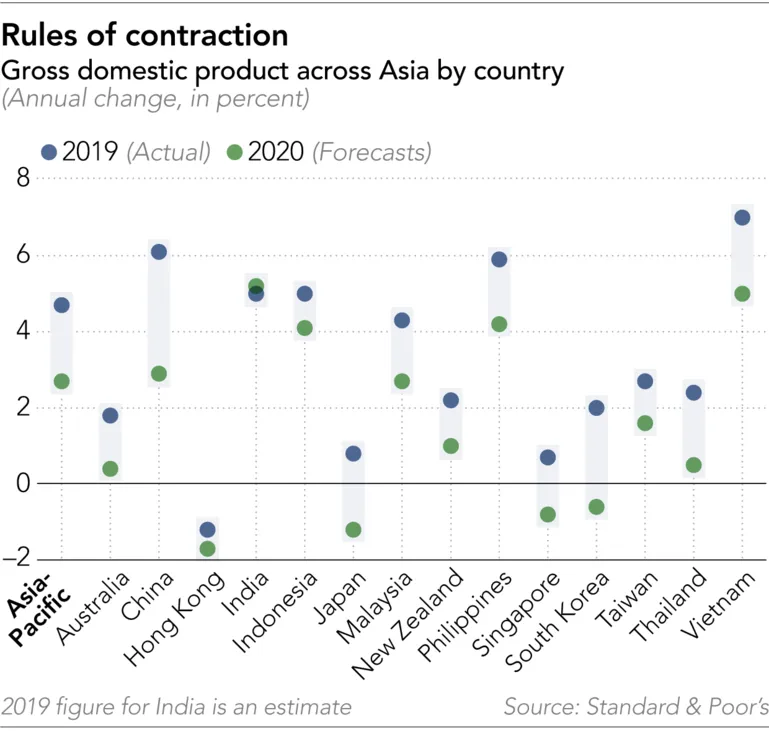

Asian economies that have relied on their openness to thrive -- as financial and corporate hubs, such as Singapore and Hong Kong; as keystones of global supply chains, such as Taiwan, Bangladesh and Vietnam; or as tourist centers, like Thailand -- have had to rapidly and comprehensively isolate themselves.

"Now what we are getting to see is an almost complete paralysis of the global economy. I think that's how I'd describe it," said Amitendu Palit, senior research fellow at the Institute of South Asian Studies at the National University of Singapore. "In my lifetime, I can't recall a situation where we have actually seen such restrictions on movements of people."

Palit, who sits on the World Economic Forum's group on trade, said that the sudden changes to global mobility are already prompting companies to rethink their supply chains.

Over the past couple of years, Southeast Asian countries, particularly Vietnam, have been able to attract manufacturers who have shifted out of China to avoid U.S. tariffs, imposed as part of the White House's "trade war" with Beijing.

Even before that, manufacturers took advantage of low tariffs between Southeast Asian countries to arbitrage labor costs and government support. A gearbox for an automobile assembled in Vietnam or India can move across borders five or six times, with value added at each stage. The pandemic could "collapse" that system, Palit said.

Workers at a factory in Hunan Province, China, individually livestream their products outdoors, as businesses find alternative ways to keep running through the pandemic. © Getty Images

Workers at a factory in Hunan Province, China, individually livestream their products outdoors, as businesses find alternative ways to keep running through the pandemic. © Getty Images Vietnam suspended inbound international flights on March 21, and banned most foreigners from entering the country the following day. The Nikkei Asian Review heard from one buyer who was suddenly unable to reach their supplier in Vietnam, and was unsure whether production was even still going on. Another buyer had canceled a trip to their factory in Cambodia -- which at the time had not imposed any restrictions and had only reported a handful of cases of COVID-19 -- citing a belief that the country was underreporting its outbreak, and a fear of getting stuck in Phnom Penh.

"There are countries like Vietnam that might be very good in terms of their promise and potential of being supply chain nodes," Palit said. "But they're not necessarily the best for ... their ability to provide an excellent public health infrastructure capable of tackling pandemic-like situations."

Already, companies are finding that shipments are being held indefinitely at ports because overstretched authorities cannot provide documentation, or because customs agents are on lockdown. As they come to terms with these emerging risks, companies are likely to try to concentrate their supply chains to as few locations and vendors as possible, and build up much bigger inventories, rather than relying on the "just-in-time" supply chains that have become prevalent over the last decade.

"This is going to leave a deep impact on the way that production is organized from now on," Palit said.

The patchwork of travel restrictions and lockdowns, as well as the suddenness of measures, has complicated businesses' planning for after the immediate crisis. Some countries took decisive action, some dithered; most that did act quickly did so in their national interest, rather than in coordination with their neighbors.

"The lack of cooperation between countries ... is the core of the problem," said Julien Chaisse, a law professor at City University of Hong Kong who studies globalization. "And I'm quite afraid that as long as there is no cooperation among them to decide when to lift these controls, the effect on the economy will be felt for quite some time."

The collapse -- even temporarily -- of supply chains will have an enormous impact on employment. The International Labor Organization has warned that 25 million jobs are at risk as a result of the pandemic. The Confederation of Trade Unions in Myanmar said that 27 textile factories in the country have shut down since the start of the crisis.

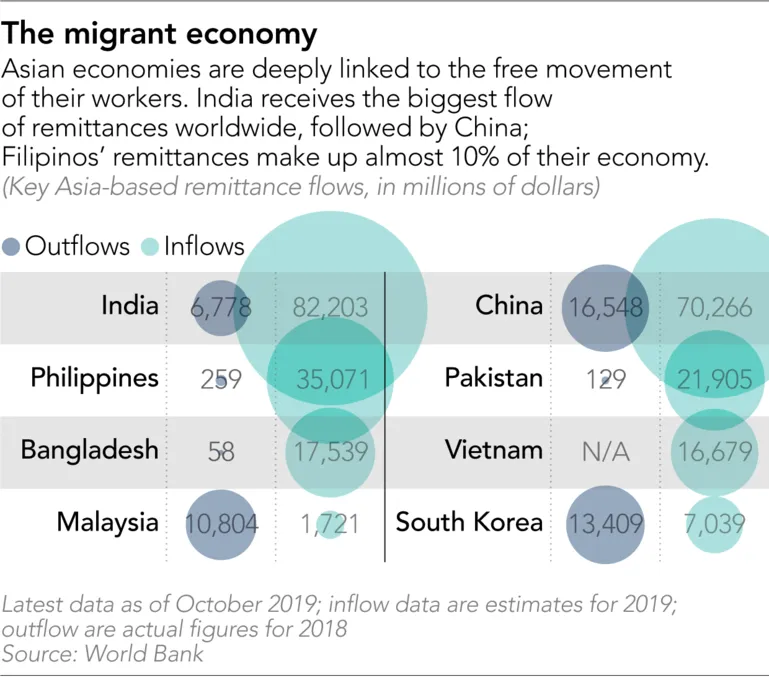

Migrant workers -- of which the ILO estimates there are more than 33 million in Asia and the Pacific -- will be particularly hard-hit. Financial flows from migrants back home make up significant contributions to economies across the region. The Philippines alone receives more than $34 billion annually from remittances.

Tens of thousands of workers from Myanmar, Cambodia and Laos have reportedly already fled Thailand. The closure of Singapore's border with Malaysia has cut thousands of people off from their jobs, to their detriment and to Singapore's. The city-state has come to rely on low-cost labor from the state of Johor to keep its manufacturing and service industries functioning.

A deserted railway station in Mumbai, India, after services were stopped to halt the transmission of the coronavirus. © Reuters

A deserted railway station in Mumbai, India, after services were stopped to halt the transmission of the coronavirus. © Reuters However, the snap ending to regional free movement will most likely hit higher-wage workers too, and could permanently undermine the status of countries like Singapore and Hong Kong, which have ridden the wave of regional integration to establish themselves as regional hubs for travel and finance. Those positions could become tenuous.

"The crisis has thrown up all kinds of jobs that we didn't think were insecure or precarious previously, but now are shown to be very much in that category," said Walter Theseira, who studies labor markets in the region as associate professor of economics at the Singapore University of Social Sciences.

Singapore's handling of the public health aspects of the emergency has been widely praised, but its economic vulnerabilities have become clear. Its airport has emptied out; its conference centers and hotels are quiet. Borders that were -- for wealthier visitors at least -- almost entirely frictionless are now closed.

"Singapore depends, to some extent, on being a regional headquarters," Theseira said. "It doesn't work as long as your high-end business people cannot move freely in the region."

No going back

Businesses that have relied on the openness of the region are trying to digest what this all means -- and what the world will look like when the pandemic is finally brought under control.

"We're in a very strange no man's land. Nothing is usual," said Sertac Yeltekin, chief operating officer of Insitor Partners, a Singapore-based social venture capital fund with investments across South and Southeast Asia. It is a business that requires frequent travel and personal contact with investors and investees. That has all ground to a halt.

"Any kind of physical proximity might lead to a contagion, so we're limiting travel, limiting seeing each other, limiting even basic personal contact," he said. "This does have impacts on business."

Like so many others, Yeltekin also has to manage the business implications of this crisis while under the emotional strain of a family spread around the world, with members in Italy and the U.S. "It's just beyond anybody's worst nightmares. It's one of those things that only happens in science-fiction movies," he said. "But as long as we keep safe and healthy, I don't care about the rest."

Unlike the financial crisis of 2008-09, this, Yeltekin said, is "a real and felt crisis," in which everyone is in some way affected.

"It's going to have far reaching effects on business, on how society is organized, on politics," he said. "We're not going back to where we were. Things are going to change profoundly."

How profoundly -- and whether for the better or the worse -- depends on the speed and effectiveness of the global response. The World Health Organization has warned that the pandemic was still accelerating in late March.

On a social and individual level, the crisis has been marked by extraordinary demonstrations of solidarity and compassion -- but also fear, nativism and scapegoating. In the U.S., President Donald Trump has used the pandemic as justification for his divisive policies on migration and trade, dubbing the coronavirus the "Chinese virus" and spreading misinformation about progress toward a treatment.

China has also run state-backed disinformation campaigns that have questioned the origins of the virus, and excluded Taiwan from vital discussions on the pandemic. Some countries, such as South Korea, have been very open with their data and transparent in their responses. Others -- even major economies like Russia -- are black boxes.

A man walks through Seoul: South Korea has been praised for its quick action and transparent handling of the disease. © Reuters

A man walks through Seoul: South Korea has been praised for its quick action and transparent handling of the disease. © Reuters Perhaps more worrying is a lack of trust within and between countries, eroded by years of rising nationalism and populist leaders who have challenged traditional institutions. In the U.S., polling from Gallup shows that political polarization is mirrored in Americans' concerns over the virus itself. Seventy-three percent of Democrats say they are worried about the outbreak, compared to just 42% of Republicans.

In late March, the G-7 group of industrialized nations was unable to even agree on a communique about the COVID-19 pandemic, reportedly because the U.S. insisted on using the term "Wuhan virus" to describe the outbreak. U.S. Secretary of State Mike Pompeo rejected this in an interview with Nikkei on Monday.

"There's not a single leader who can convene others. It shows the kind of world we're living in," said Syed Munir Khasru, chairman of the Institute for Policy, Advocacy, and Governance, a Dhaka-based think tank. "You have a highly interconnected world, thanks to technology, with all these great advances and benefits -- you and I looking at each other across thousands of miles -- but on a philosophical and ideological level, it has never been as disconnected. ... The real crux of the thing, the leadership, it has never been as disjointed."

Chalked circles put distance between people in line to pick up medicine in Kolkata, India. © Reuters

Chalked circles put distance between people in line to pick up medicine in Kolkata, India. © Reuters "I think there will be a natural tendency toward trying to withdraw, more insularity. And this will be exploited by nationalist politicians," said Ian Goldin, professor of globalization and development at Oxford University, and co-author of "The Butterfly Defect: How Globalization Creates Systemic Risks, and What to Do About It."

To do that would be "totally counterproductive," Goldin said. Managing this crisis and the recovery will need the engine of globalization to be restarted.

"We are going to need not only a medical response internationally -- we are going to need an economic response internationally, and ... a response which rebuilds globalization, in the sense of rebuilding continental travel and tourism and trade," Goldin said. "In the way it changes our priorities and our thinking, it's more like a war than an economic crisis."

Goldin echoed a sentiment expressed by almost everyone that Nikkei spoke to in researching this story, from economists to investors, health care professionals to politicians. What this crisis has revealed is a frightening vacuum of leadership.

"We could stop this. Like we could stop the financial crisis, we can stop climate change. We can stop all these risks. But whether we do or not is a political choice," he said. "There is no wall high enough that will keep out a pandemic. What the wall will keep out is the ability to cooperate, the skills and the other things that we desperately need. It's vital that we learn that lesson."