Yet challenges remain—especially as the population surges and vehicle use skyrockets. In an insightful conversation with Saigon Investment, Dr. NGUYỄN HỮU NGUYÊN, a senior expert from the HCMC Urban Planning and Development Association, shares his perspective on where the city has been and where it needs to go.

Journalist: - Dr. Nguyên, looking back over the past 50 years, how would you describe the evolution of HCMC’s transport infrastructure?

DR. NGUYỄN HỮU NGUYÊN: - Right after 1975, Ho Chi Minh City actually had a decent foundation. Its streets were generally wider and longer than those in Hanoi, and traffic was manageable due to a smaller population—just over 2 million. However, during the following decade, the city was focused on overcoming a major socio-economic crisis. There were very limited resources for infrastructure, and although traffic volume grew, it didn’t yet cripple the system.

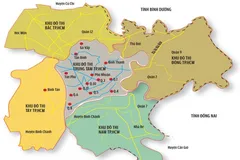

Things started to shift in the late 1980s after Vietnam launched its economic reforms. The move to a market-oriented economy triggered rapid urban growth. The city’s population surged to nearly 10 million, and with that came millions of private vehicles. But while vehicles multiplied, roads didn’t. Urban land in the city center was already maxed out, so traffic bottlenecks became increasingly common.

That said, progress has been made. We've seen the introduction of modern infrastructure—flyovers at key intersections, widened roads, and of course, Metro Line 1 which stretches nearly 20 kilometers. Still, we can’t ignore the fact that transportation remains a lingering headache. Just recently, the city tasked the HCMC Institute for Development Studies to look into how traffic infrastructure can be better synchronized with housing development. That’s a step in the right direction.

- Urban traffic used to be one of the seven major breakthrough programs in the city’s strategic plan. Has it lived up to expectations?

- Not quite. The pace of improvement has been too slow. Despite several major initiatives—including the well-known sidewalk clearance campaign—traffic congestion persists and sometimes worsens. The core issue is structural: Ho Chi Minh City has devoted too little of its land to transportation. Ideally, 20% of urban land should be allocated for transport. We barely hit 10%.

Pair that with the current traffic load—over 7 million motorbikes and more than 1 million cars—and you get a recipe for daily gridlock. It’s like trying to channel a massive river through a narrow stream: flooding is inevitable. This isn’t just a traffic problem—it’s a symptom of an overstretched urban system, with too many people and too little space.

Now, we can’t just reduce the population or limit personal transport. That’s not realistic. Many workers rely on motorbikes for their livelihoods. But we can introduce smarter, space-efficient solutions. Multi-level and underground parking structures are a must. Elevated rail systems, better use of the river network for public transport, and a stronger digital backbone using AI to manage traffic—all of that can make a real difference.

- The recently approved development plan envisions HCMC as a global megacity with 14 to 15 million residents by 2050. What's your take on this vision?

- Ambitious? Yes. But also necessary, if we’re being realistic. Ho Chi Minh City is the nucleus of the Southern Key Economic Zone, and that role comes with responsibilities. It must not only lead in finance and industry but also act as a hub for technology, logistics, and urban innovation. That means a two-way relationship with the surrounding provinces: the city exports capital, know-how, and infrastructure models; in return, it imports labor, raw materials, and trade.

But the target population of 15 million raises red flags. We need to study what megacities around the world are going through. Cities like Jakarta, Manila, and even Los Angeles—all struggle with housing shortages, environmental stress, and uneven access to public services.

Rather than chasing numbers, we should shift the focus. The mark of a truly modern city isn’t just its size. It’s the quality of life it offers. Livability—clean air, green space, efficient public services, accessible housing—that’s the real endgame. In that sense, traffic reform isn’t just about roads. It’s about shaping a city that people actually enjoy living in.

- Final thoughts?

- We stand at a crossroads. The city has grown remarkably—but now we need a shift in mindset. Infrastructure must go hand in hand with urban planning. It’s not just about building more roads, but about building smarter. If we get that right, we won’t just keep traffic moving—we’ll keep the city moving forward.

Another important point we often overlook is how transport impacts social equity. In a city this big, mobility determines opportunity. If people can't get to work, school, or healthcare efficiently, the gap between rich and poor widens. Investing in a better transit system is not just about easing traffic—it's about giving every resident a fair shot at a better life.

And let’s not forget climate resilience. With climate change accelerating, HCMC is facing real threats—flooding, heatwaves, rising sea levels. Green transport infrastructure, like electric buses and improved sidewalks for pedestrians and cyclists, must be part of our long-term strategy. These are not just luxuries—they’re survival tools for a sustainable future.

Ultimately, transport infrastructure is the backbone of urban development. It's not glamorous, and it's often invisible when it works well—but when it fails, everyone feels it. Ho Chi Minh City’s next chapter depends on how boldly and intelligently we choose to build that backbone.

- Thank you very much, Dr. Nguyên.