At the heart of this initiative lies a dual strategy: consolidating provincial boundaries to form large-scale growth zones, and introducing a streamlined two-tier local government system that would decentralize authority while improving public service delivery. This ambitious undertaking is not just a matter of redrawing lines on a map; it is about redefining the way Vietnam plans, governs, and grows.

The potential implications are far-reaching. By aligning administrative units with geographic, economic, and cultural realities, Vietnam aims to foster regional integration and efficiency, overcome fragmentation, and build more competitive urban economies. In parallel, institutional reforms promise to remove bureaucratic bottlenecks and empower grassroots units, laying the foundation for a governance system that is more agile, transparent, and citizen-focused.

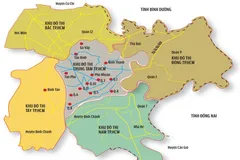

One of the most striking proposals is the expansion of Ho Chi Minh City to incorporate parts of Binh Duong and Ba Ria - Vung Tau. If realized, this merger would create a mega-urban area comparable in scale and dynamism to the world’s top metropolitan regions. It is an ambitious plan, but one that reflects Vietnam’s growing confidence and determination to leap forward.

Toward a Unified Growth Model

For decades, Vietnam’s provincial system has been characterized by fragmentation and competition. Each province has operated as a relatively autonomous planning unit, crafting its own strategies and investment agendas. While this model provided a measure of flexibility, it also led to inefficiencies, duplicated efforts, and a lack of regional cohesion. Provincial boundaries often ignored the economic and logistical interdependencies that naturally connect neighboring areas. As a result, development has frequently been piecemeal, and infrastructure investments have not always aligned with broader regional needs.

The current reform effort seeks to replace this model with a more holistic and coordinated approach. By merging provinces with shared economic characteristics, complementary industries, and cultural affinity, Vietnam hopes to create larger, more capable administrative entities that can pursue integrated development strategies. These new regional structures would be better positioned to attract large-scale investment, manage infrastructure networks, and deliver public services effectively.

The proposed merger of Quang Nam and Da Nang, for example, would unify two regions that already share historical ties and economic interdependence. Currently, the two provinces compete in attracting investment to coastal developments and industrial zones, often leading to inefficient land use and missed opportunities for collaboration. Uniting them under a single planning framework would allow for more rational allocation of resources, joint development of infrastructure, and coordinated promotion of tourism, technology, and logistics.

A similar case can be made for the proposed consolidation of Tra Vinh, Vinh Long, and Ben Tre in the Mekong Delta. Each of these provinces contributes distinct strengths: Tra Vinh with its seaport and renewable energy potential, Ben Tre with its agricultural depth, and Vinh Long with its inland connectivity and strategic location. As a unified province, they could form a powerful agro-economic cluster that capitalizes on riverine transport links to Ho Chi Minh City and international markets. This would create a seamless eco-economic zone that integrates production, logistics, and export.

Nowhere, however, is the potential for regional synergy more evident than in the greater Ho Chi Minh City area. Merging the city with Binh Duong and Ba Ria - Vung Tau would form a unified economic corridor stretching from the urban core to industrial and maritime zones. Together, these three provinces already account for a significant portion of Vietnam’s GDP and state budget revenue. Each brings distinct strengths: Ho Chi Minh City as a financial and service hub, Binh Duong as an industrial dynamo, and Ba Ria - Vung Tau as a maritime and energy center.

The integration of these localities would enable comprehensive regional planning on a scale Vietnam has not previously attempted. Urban growth could be managed more sustainably, infrastructure systems could be designed with interconnectivity in mind, and resources could be allocated based on regional priorities rather than provincial silos. Crucially, such integration would allow for the coordinated development of transportation networks, including expressways, metro lines, airports, and seaports. The logistical corridor linking Cat Lai and Cai Mep ports, for instance, could be optimized to support both domestic trade and international shipping, while the Tan Son Nhat–Long Thanh axis could become the backbone of regional air transport and freight movement.

The vision is not merely about urban expansion. It is about building an integrated, future-ready metropolis where industry, logistics, services, and innovation converge. Such a transformation would elevate Vietnam’s standing in the global economic hierarchy and position the southern region as a key engine of growth for the entire country.

Building Governance for the People

Spatial reorganization alone, however, is not sufficient to drive development. Without accompanying institutional reform, new administrative boundaries risk becoming symbolic rather than substantive. Recognizing this, Vietnam is also pursuing a deep restructuring of its governance architecture, centered around the shift to a two-tier system consisting only of provinces and communes or wards.

This model promises to enhance both efficiency and responsiveness by removing the district level, which has often served as a bureaucratic bottleneck. Under the new structure, provincial governments would assume strategic planning and coordination functions, while communal-level units would be directly empowered to serve citizens and manage public services.

This transition marks a conceptual shift in the role of government—from a top-down apparatus to a more horizontal, networked system of decision-making. Grassroots authorities, previously seen as mere executors of policy, would be redefined as key agents of public service delivery. To fulfill this mandate, they will require significant capacity-building, including training in administrative processes, community engagement, and digital tools.

Technology will play a central role in this transformation. Electronic governance platforms, real-time data systems, and online citizen feedback channels will be essential for ensuring transparency and accountability. Provinces will need to build institutional capabilities for policy design, data analysis, and scenario planning, while also establishing rapid-response mechanisms that can adapt to local needs.

This governance reform is not just about efficiency. It is about cultivating a sense of ownership and agency among both officials and citizens. When communal governments are empowered to respond quickly to local challenges, and when citizens feel heard and respected, trust in the state is strengthened. This, in turn, creates a more fertile environment for innovation, investment, and social cohesion.

Importantly, the restructuring of governance also supports the broader objective of breaking down parochial mindsets. As localities become more interconnected and interdependent, the logic of “my province first” gives way to a regional consciousness rooted in shared interest and mutual benefit. Citizens begin to see themselves not just as residents of a particular administrative unit, but as stakeholders in a larger development community.

This psychological shift is perhaps the most powerful outcome of reform. When people no longer perceive public goods—such as hospitals, schools, industrial parks, or ports—as confined by provincial borders, they begin to engage more openly with the broader system. Local governments, in turn, can plan infrastructure and services based on real demand, rather than arbitrary administrative lines.

Such changes expand not only physical space for development but also the emotional and intellectual space in which citizens imagine their futures. This is what some have called the “development space in people’s hearts”—a zone of possibility that emerges when institutions become inclusive, transparent, and aligned with the aspirations of those they serve.

Navigating the Risks of Reform

As with any major reform, the risks are real and must be acknowledged. Merging administrative units carries the danger of institutional mismatch. Provinces with different governance styles, resource endowments, or development priorities may struggle to find common ground. Without a strong coordinating authority, new administrative units may fall into internal competition, undermining the very goals of integration.

There is also the risk of declining service quality, particularly in rural or remote areas, if local units are not adequately empowered or supported. The removal of district-level administrations could lead to gaps in oversight or confusion about roles and responsibilities. Citizens in smaller communes may find it harder to access information or navigate bureaucratic processes.

Institutional resistance is another major hurdle. Civil servants accustomed to the old system may view reforms as a threat to their authority or job security. Mergers may lead to conflicts over personnel decisions, resource allocation, and political influence. If not managed transparently, these tensions could delay implementation and erode public trust.

Moreover, administrative restructuring alone does not guarantee better outcomes. Without parallel investment in institutional capability, digital infrastructure, and public participation, reform could lead to a bloated bureaucracy with limited effectiveness.

To mitigate these risks, a comprehensive and phased approach is essential. Regional master plans must be rooted in shared visions and realistic assessments of local conditions. These plans should prioritize interconnectivity and joint benefit, avoiding duplication and ensuring that investments are balanced across urban and rural areas.

Public service delivery must be reimagined to accommodate the complexity of larger jurisdictions. This may include creating satellite administrative centers, enhancing digital access, and giving commune-level governments real authority over budgets, personnel, and decision-making.

Equally important is managing the transition of human resources. Officials at dissolved district levels must be reassigned or retrained through clear and transparent criteria, ensuring fairness and minimizing disruption. Oversight mechanisms, both internal and from civil society, must be strengthened to ensure accountability and maintain public confidence.

Above all, reform must be accompanied by effective public communication. Citizens need to understand not only what is changing, but why it matters—and how it will improve their daily lives. Building a broad consensus around reform is critical to overcoming resistance and ensuring that new institutions are rooted in legitimacy.

If these reforms are carried out transparently, inclusively, and strategically, they could mark a turning point in Vietnam’s development trajectory. By creating a more coherent, collaborative, and people-centered governance system, the country will be better equipped to navigate the complexities of a rapidly evolving global economy.

This is not just a technical adjustment. It is a profound reimagining of how a nation plans, governs, and grows. And if successful, it could offer a model for other emerging economies seeking to balance decentralization with integration, growth with equity, and efficiency with participation.