Together, they would form a vast, integrated metropolitan region of nearly 14 million people with a combined GDP contribution that rivals some of Southeast Asia’s most advanced urban economies.

This potential "Greater HCMC" is not simply a regional restructuring effort. It is an attempt to reimagine Vietnam’s economic geography for the 21st century—an opportunity to unlock new growth dynamics, reposition Vietnam within global supply chains, and build a more inclusive, innovation-driven, and resilient economy. But this vision hinges on one key factor: a sharp and sustained improvement in Total Factor Productivity (TFP).

TFP—often considered the “holy grail” of economic competitiveness—is what remains of growth once inputs like labor and capital have been accounted for. It is a measure of how efficiently and effectively an economy deploys its resources. And in the case of the new metropolitan HCMC, it must be the fulcrum of every development strategy moving forward.

A Megacity in Numbers—and in Purpose

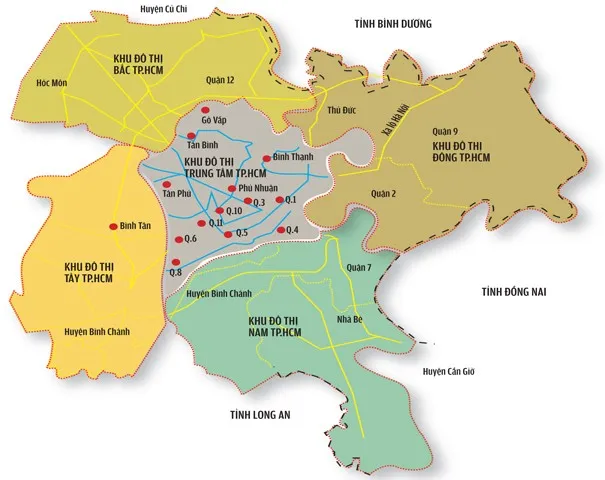

The scale and stakes are immense. The merged region would span 6,770 square kilometers, with a projected population of 13.7 million. In 2024, their combined state budget contribution stood at approximately VND 678 trillion, or nearly 40% of Vietnam’s total. It would bring together three economic powerhouses with complementary roles: HCMC as the financial and service core, Binh Duong as the industrial workhorse, and Ba Ria–Vung Tau as the strategic maritime and energy hub.

Yet, disparities persist. In Q1 2025, HCMC led growth at 7.51%, followed by Binh Duong at 6.74%, while Ba Ria–Vung Tau lagged at 2.48%—or a contraction of 2.55% if excluding the oil and gas sector. These numbers highlight the uneven development landscape and the pressing need for integrated policy responses that go beyond sectoral or provincial silos.

Moreover, HCMC is showing signs of global slippage. In 2024, the city dropped eight places in global urban rankings to 102nd, falling behind regional counterparts such as Bangkok, Kuala Lumpur, and Jakarta. These declines not only reflect shortcomings in infrastructure and service quality but also speak to the broader challenge of keeping pace in a fiercely competitive global urban hierarchy.

To reverse this trajectory and build a future-ready city-region, the research team at the University of Economics HCMC has proposed five interlinked strategic pillars that target both structural bottlenecks and untapped growth potential.

Pillar 1: Building the Smart and Sustainable City

Urban infrastructure is the bedrock of productivity—and currently one of HCMC’s weakest links. A modernized, smart, and green infrastructure framework is essential to enable the seamless flow of goods, people, and capital.

Transit-Oriented Development (TOD) must become the dominant urban planning model. With Metro Line 1 (Ben Thanh–Suoi Tien) nearing completion, the next step is extending it into Binh Duong and other outlying areas. The full integration of public transport across provinces—backed by unified fare systems, smart ticketing, and real-time mobility platforms—will ease congestion and improve urban efficiency.

Ring Roads 2, 3, and 4, as well as 59 identified strategic projects, must be fast-tracked to connect industrial clusters with ports, airports, and residential zones. Delays in these projects are not mere inconveniences—they translate directly into higher logistics costs, productivity losses, and investor hesitation.

In tandem, new urban areas should embrace eco-smart zoning. Satellite cities designed with environmental sustainability in mind—notably those in Cu Chi, Can Gio, and Long Thanh—can help decongest the urban core while enhancing quality of life. Smart water, waste, and energy systems must be integrated from the start. Digitally enabled governance—featuring AI-powered service delivery and predictive urban maintenance—should underpin this transformation.

A lesson can be drawn from Seoul’s Songdo City, a planned smart city that has successfully embedded green design, tech integration, and livability standards from the ground up.

Pillar 2: The Innovation and Entrepreneurship Imperative

No global city achieves sustained competitiveness without a dynamic innovation ecosystem. For Greater HCMC, innovation must become the defining characteristic of its next growth phase.

This means creating fertile ground for startups, tech firms, and high-tech manufacturing. But innovation ecosystems don’t emerge organically; they require deliberate, patient investment in research institutions, human capital, and innovation infrastructure.

A central policy challenge is bridging the gap between universities and industry. Applied research in AI, logistics, biotech, and climate tech must be incentivized and supported through funding channels that reward commercialization. Tech parks and co-working campuses—like the emerging Thu Duc Innovation Hub—should be scaled and replicated across districts with unique thematic orientations.

Access to capital also needs reform. Vietnam’s venture capital ecosystem remains shallow compared to peers in Singapore or Indonesia. The establishment of a regional Innovation Investment Fund, with a mix of public and private participation, could unlock the capital pipeline for early-stage enterprises.

Finally, immigration policy must be aligned with innovation goals. A streamlined visa regime for global tech talent, digital nomads, and scientific collaborators will be essential to diversify the talent pool and raise the city’s intellectual capital.

Pillar 3: Logistics, Services, and the Maritime Economy

Geography is Greater HCMC’s strategic advantage. Its proximity to deep-sea ports, industrial hinterlands, and Southeast Asian trade routes gives it enormous potential to become a regional logistics and maritime hub.

Cai Mep–Thi Vai Port already handles some of Vietnam’s largest container volumes, but last-mile connectivity remains a chokepoint. Investments in inland container depots (ICDs), digital port platforms, and port-hinterland corridors—particularly connecting to Binh Duong and Dong Nai—will be critical.

HCMC must also move up the logistics value chain. This means not only moving goods efficiently but adding value through integrated services like cold-chain logistics, reverse logistics, and logistics-as-a-service platforms. Ba Ria–Vung Tau, with its extensive coastline and energy base, should be developed into a dual-purpose maritime cluster that combines industrial port functions with marine tourism, aquaculture, and renewable energy logistics.

In services, finance, health, and education must become globally competitive exports. The creation of special economic zones or sectoral free zones—where regulatory flexibility is granted—could accelerate this transition. International partnerships with institutions in Japan, Australia, and the EU could be leveraged to build high-standard service platforms.

Pillar 4: Deepening Regional and Global Integration

The fourth pillar revolves around regional connectivity—not just in physical infrastructure but in strategic alignment. The Southeast region must plan and invest as a single economic space, not a patchwork of disconnected provinces.

This requires harmonized infrastructure planning, inter-provincial regulatory alignment, and joint investment promotion. The HCMC–Moc Bai Expressway and Long Thanh International Airport must be viewed not as local megaprojects but as regional game-changers.

Crucially, digital connectivity must be a priority. 5G networks, data centers, and AI-enabled logistics systems can reduce operating costs and allow local firms to plug into global value chains more efficiently.

Integration with the East-West Economic Corridor (EWEC) and Southern Economic Corridor (SEC) should be fast-tracked. These corridors can position HCMC as a gateway for intra-ASEAN trade, linking Vietnam’s industrial base with Cambodia, Thailand, and Myanmar.

International memoranda of understanding (MOUs) with peer cities—such as Busan, Osaka, and Rotterdam—could facilitate knowledge exchange in smart port operations, sustainable urban development, and logistics innovation.

Pillar 5: Institutional Reform and Special Mechanisms

Perhaps the most important, and politically sensitive, pillar involves reforming the city’s governance model. For Greater HCMC to function effectively, it cannot operate within a rigid, fragmented, or outdated administrative system.

Resolution 98 (2023) offers a window of opportunity. By granting HCMC greater fiscal autonomy, streamlined investment approvals, and more flexible land-use mechanisms, it allows for experimentation and innovation in urban governance. The resolution should be expanded in both geographic and functional scope to cover the entire integrated region.

The integration of Ho Chi Minh City, Binh Duong, and Ba Ria–Vung Tau is more than a merger. It is a national wager on a new model of urban-led, productivity-driven growth. Its success—or failure—will reverberate far beyond Vietnam’s borders.

Inter-agency coordination remains a chronic challenge in Vietnam. A unified Metropolitan Governance Council—with delegated authority from the central government—could oversee infrastructure planning, spatial development, and investment prioritization across the three provinces.

Equally, local public sector capacity must be strengthened. Digital procurement systems, performance-based budgeting, and participatory urban planning processes should be institutionalized to raise transparency and accountability.

In parallel, policy stability and regulatory predictability are critical. Investors require long-term clarity on taxes, land rights, and infrastructure pipelines. Without these, even the most ambitious development plans may falter in execution.

Long-Term Vision: From National Champion to Global Contender

Beyond 2030, the aspiration is for the unified Ho Chi Minh City to emerge as a global city—an influential node in the international economy, not just a domestic champion. To achieve this, the city must continuously benchmark itself against global leaders like Singapore, Seoul, Barcelona, and Toronto.

The roadmap includes building a credible International Financial Center (IFC), with its own legal framework, governance board, and strategic links to global capital markets. Tax incentives, a fintech sandbox, and visa fast-tracks will be necessary—but so too will be deep reforms in legal infrastructure, digital trust frameworks, and cross-border capital mobility.

Climate resilience must also rise on the agenda. With large parts of the city vulnerable to flooding and sea-level rise, sustainability planning—including green infrastructure, sponge cities, and renewable energy transitions—must be fully embedded into long-term urban development.

Ultimately, Greater HCMC’s success will depend on its ability to transform institutional intent into execution capacity. The next five years are crucial. If Vietnam gets it right, the unified megacity could become the new symbol of Southeast Asia’s economic renaissance—a future-ready metropolis defined not by size alone, but by intelligence, agility, and ambition.