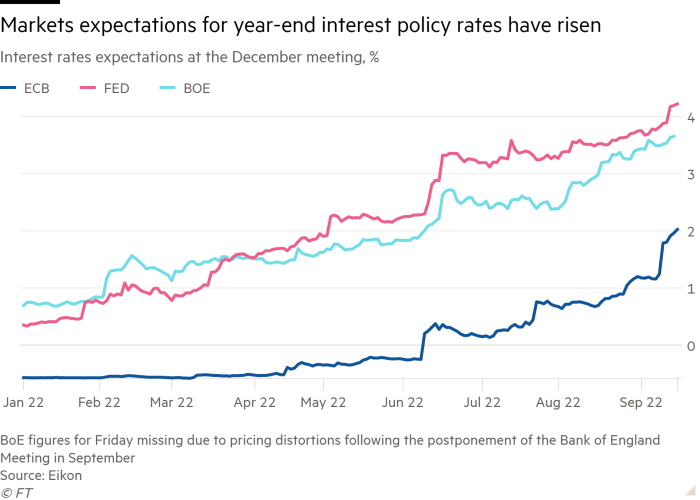

Investors are pricing in a sharper surge in interest rates over the coming months after the world’s major central banks strengthened their resolve to tackle soaring prices, signalling they would prioritise inflation over growth.

A Financial Times analysis of interest rate derivatives, tracking expectations for borrowing costs in the US, UK and eurozone, showed markets expect a more drastic pace of tightening during the final quarter of 2022 than they did earlier this year.

The shift in mood comes ahead of crucial policy meetings by the US Federal Reserve, the Bank of England, the central banks of Norway and Sweden, and the Swiss National Bank this week. It follows a poor August inflation reading in the US and warnings from monetary policymakers on both sides of the Atlantic that they were becoming increasingly concerned that, without substantial rate rises, high inflation would prove hard to shift.

The mounting expectations that central banks will increase rates, even if their economies fall into recession, has prompted concern from the World Bank. The Washington-based organisation warned last week that policymakers risked sending the global economy into recession next year.

“Central banks will sacrifice their economies to recession to ensure inflation quickly returns to their targets,” said Mark Zandi, chief economist of Moody’s Analytics. “They understand that if they don’t, and inflation becomes more entrenched, this will ultimately result in a more severe downturn.”

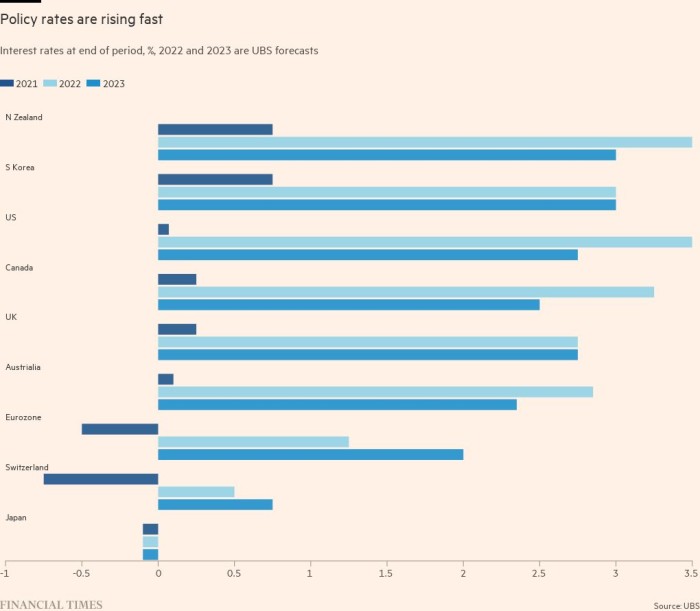

Since June, the world’s 20 major central banks have together raised interest rates by 860 basis points, according to FT research.

As of Friday, markets were pricing in a 25 per cent chance that the US Federal Reserve would raise rates by 100 basis points on Wednesday and expected the federal funds target to be above 4 per cent by the turn of the year — about one full percentage point higher than in early August.

Markets expect the European Central Bank’s deposit rate to hit 2 per cent by the end of the year, up from 0.75 per cent now. The latest bet is more than one percentage point higher than what investors were forecasting in early August. Philip Lane, ECB chief economist, told a conference at the weekend that he expected it to raise rates “several” more times this year and early next year. He said this was likely to involve some “pain” of lost growth and jobs to bring down demand, reflecting the ECB’s rising concern that inflationary pressures are spreading from energy and food to other products and services.

Switzerland’s central bank is expected to raise its policy rate by 75-100 basis points next Thursday, ending a seven-year experiment with negative interest rates.

Paul Hollingsworth, chief European economist at BNP Paribas, said central banks were “front-loading their tightening cycles” despite signs that growth was weakening.

A big shift in market expectations came after policymakers, such as Federal Reserve chair Jay Powell and ECB executive board member Isabel Schnabel, delivered hawkish messages at the Kansas City Fed’s annual Jackson Hole conference in late August.

“That sucking sound you hear is the sound of policymakers pulling rate hikes previously expected to take place in 2023 into 2022,” said Krishna Guha, vice-chair at the investment banking advisory firm Evercore ISI, following the meeting. “We are ending up globally with something that — looking across 2022 as a whole — will resemble more of a scrambled level shift than a conventional tightening cycle.”

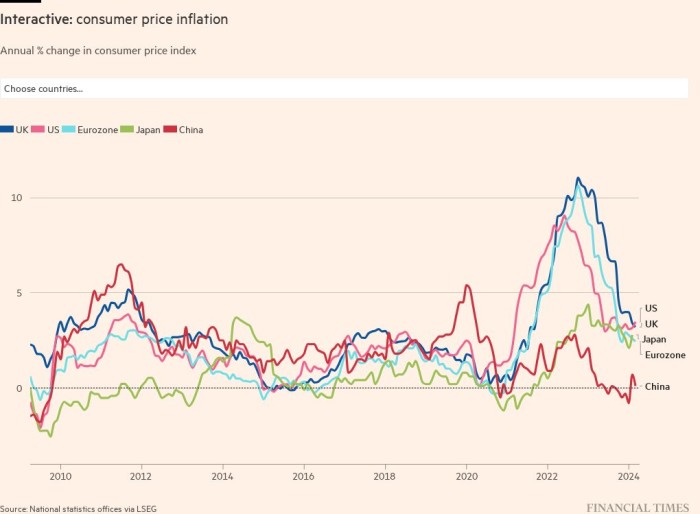

Since Jackson Hole, US inflation has proved to be stickier than expected, coming in at an annual rate of 8.3 per cent in August. In the eurozone, price pressures are expected to hit double digits in the coming months. The UK government’s £150bn energy support package will lower inflation in the short term, but boost price pressures in the medium term by bolstering demand.

While most of the inflation seen in Europe remains the result of the surge in energy prices triggered by the war in Ukraine, there have been increasing signs in both the single currency area and the UK that price pressures have become more widespread and more entrenched.

“Ordinarily, central banks would look through gains in these volatile prices as temporary,” said Jennifer McKeown, head of global economics at Capital Economics. “But in an environment where core inflation is already high and inflation expectations and wage negotiations seem to be following energy prices higher, monetary policymakers just can’t take that risk.”