Evawangi, a doctor at a public hospital on the outskirts of Jakarta, grows more worried every day.

Her hospital has seen an increase in suspected coronavirus patients admitted over the past two weeks, but it is quickly running out of protective gear for staff members. Many are donning cheap plastic raincoats to shield themselves from the virus.

"We prioritize the N95 and surgical masks, hazmat suits, face shields for those in the emergency unit and isolation ward," Evawangi told the Nikkei Asian Review last week. "Our supply is limited; we can only restock it day by day. Now we have just 40-50 sets [of gear] when our actual need is 80 sets daily."

Evawangi's story is far from unique. All over Indonesia's social media and news reports, photos and footage show doctors and nurses clad in blue or green raincoats. Around half the country's 2,491 confirmed cases as of Monday are in Jakarta, but others are scattered across nearly all 34 provinces.

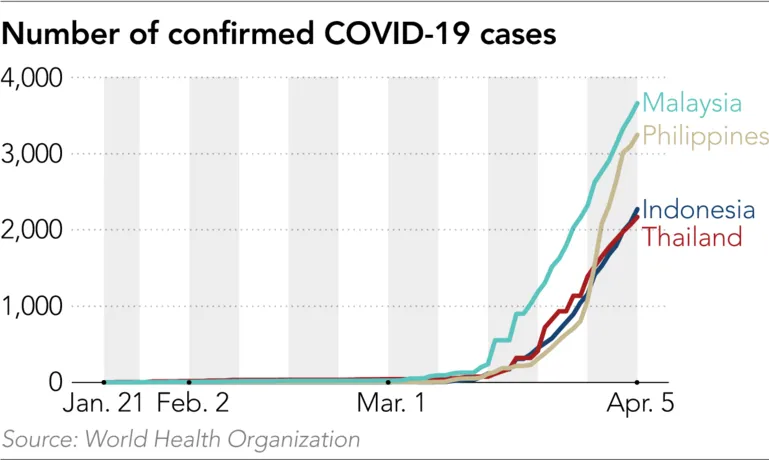

The worst may be yet to come. As China's case count has slowed, Europe and North America have become the new coronavirus crisis zones. But Southeast Asia has also seen a rapid escalation, raising concerns that the region of over 650 million people could be the next hotbed. Countries with resource-starved health care systems, such as Indonesia and the Philippines, are considered the most at risk.

The Indonesian Doctors Association has urged the government to guarantee protection of medical personnel, advising workers to avoid treating COVID-19 patients without proper safeguards. Already, at least 18 association members have died in the outbreak, while nearly 100 health workers have been infected in Jakarta alone.

The government said it has distributed hundreds of thousands of pieces of protective equipment nationwide, but the gear remains scarce, forcing many hospitals to ask for donations of simple supplies like gloves and hand sanitizer.

"Make this a war that we can win, not a suicide mission," one hospital posted on Twitter.

Due to their close links to China, more than half of Southeast Asian nations -- including Thailand, Malaysia, Singapore and Vietnam -- had reported their first cases by late January. Yet, their numbers grew slowly at first. Hanoi was even on the verge of declaring an end to the epidemic in early March.

Then came the second wave and exponential growth.

In Vietnam, which imposed strict quarantine measures on both residents and visitors in February, this new wave has been linked to an influx of international arrivals -- led by tens of thousands of citizens rushing home following lockdowns overseas.

In Thailand, local clusters started cropping up in Bangkok in March -- including one at a nightclub as well as the army-owned Lumpinee Boxing Stadium, which hosted a Thai kickboxing event on March 6. Over half the 2,220 confirmed cases in Thailand, as of Monday, were in Bangkok and its vicinity.

A Muay Thai kickboxing event in mid-March: A similar event in Bangkok spawned a coronavirus cluster. (Photo by Akira Kodaka)

A Muay Thai kickboxing event in mid-March: A similar event in Bangkok spawned a coronavirus cluster. (Photo by Akira Kodaka) In Malaysia, a gathering of 16,000 people at Sri Petaling mosque outside Kuala Lumpur appears to have created a major cluster. Significant numbers of visitors from Thailand and Indonesia attended the event.

And in the other direction, Indonesia is bracing for an influx of migrant workers returning from Malaysia, as well as nearly 12,000 ship crew members from across the globe. Another worry is the upcoming Islamic fasting month of Ramadan, which begins in late April and typically involves millions of Indonesians traveling to their hometowns.

Initially, some had hoped Southeast Asia's tropical climate would be an advantage, since the SARS outbreak in 2003 petered out after the weather warmed up. Another perceived edge was the region's generally young population, compared with Italy or the U.S., as COVID-19 typically hits elderly the hardest.

But these notions have been called into question. Indonesia is a case in point. Its confirmed cases are far below the U.S. and Italian tallies, but its fatality rate, 9%, is one of the highest in the world.

"Age is not the only factor in high fatality," said Pandu Riono, an epidemiologist at the University of Indonesia. "Even though we have a young population, many are smokers or have underlying illnesses such as hypertension and diabetes. That makes the virus more deadly."

A lack of preparation is likely making matters worse. Indonesian officials had downplayed the threat before the country's first cases were detected on March 2. Poor testing capacity means delayed diagnosis and patients being rushed to hospital too late -- which may also explain the high death rate.

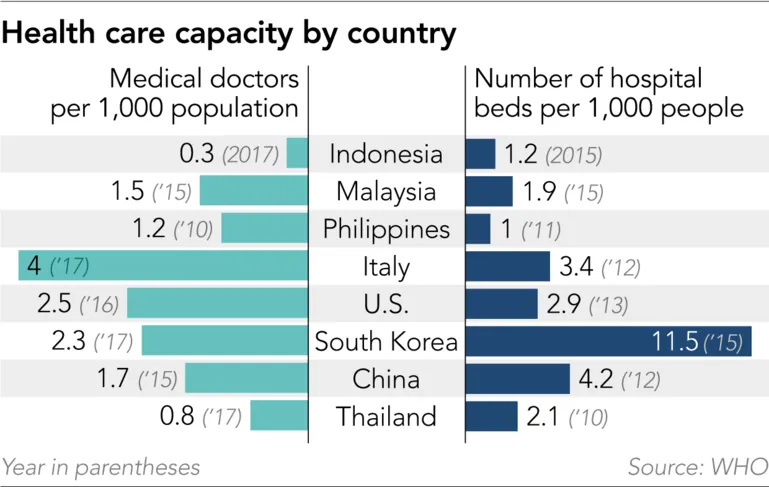

"Our health care system has limited capacity," Riono said. "Many of those who need treatment can't be treated, so the system let them die. Isn't that sad? It's possible we may become like Italy."

Recent math modeling by Riono and his peers suggested the actual number of infections in Indonesia may have already reached 1 million, only 2% of which have been detected. The number of deaths also could be much higher than the latest toll of 209. Numerous deaths in Jakarta and elsewhere are suspected to be COVID-19 cases but could not be confirmed due to delayed test results.

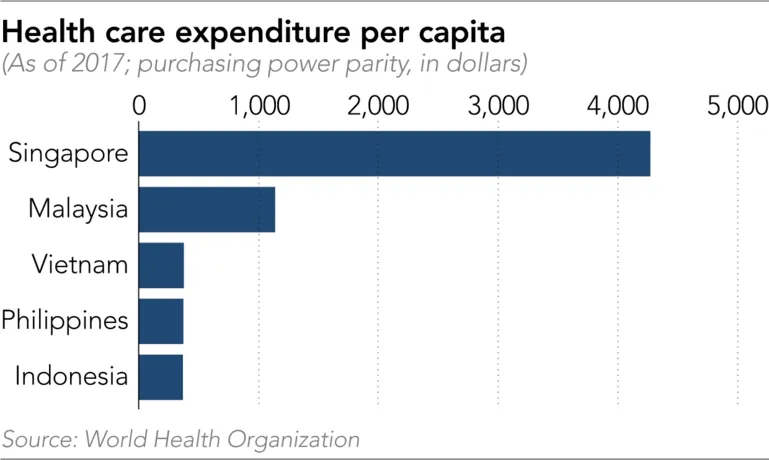

Compared with other major economies in the region, Indonesia has the lowest health spending per capita, and the lowest number of doctors, at just 3 per 10,000 people.

Additionally, the Indonesian government is probably the most reluctant to apply tough measures to restrict public movement.

The Philippines has imposed a monthlong lockdown on its main island of Luzon, home to 60 million people, with the army helping to enforce it. Malaysia closed its borders and shut down nonessential businesses in mid-March, slapping fines on violators. Singapore has gone from ordering 14 days of isolation for visitors from neighboring countries and elsewhere to barring entry altogether and ordering workplaces and schools to shut, effective Tuesday.

Thailand has introduced even more draconian policies, such as curfews and restrictions on speech, with Prime Minister Prayuth Chan-ocha saying this is a time to put "health before freedom." Cambodia appears headed in a similar direction.

Workers disinfect the entrance to the Sri Petaling mosque in Kuala Lumpur in late March. A significant number of the country's cases have been linked to an event at the mosque. © EPA/ Jiji

Workers disinfect the entrance to the Sri Petaling mosque in Kuala Lumpur in late March. A significant number of the country's cases have been linked to an event at the mosque. © EPA/ Jiji Indonesia, however, only banned international arrivals last Thursday. And while most offices, shopping malls and public places in greater Jakarta have been shut over the past few weeks, authorities only urge residents to limit their comings and goings with no enforcement.

President Joko Widodo has declared a national public health emergency but is reluctant to stifle the economy any more. "We cannot just imitate [other countries], because every country has its own characteristics," he said.

London-based consultancy TS Lombard, which has compared the outbreak responses of Indonesia, the Philippines and Thailand, said Southeast Asia's largest economy is "the worst positioned to contain the virus."

"The combination of less rigorous social distancing measures and a weak health care service means that Indonesia is the least likely of the three countries ... to stop the spread of the virus anytime soon," analyst Krzystof Halladin said in a note.

Yet, even better-equipped countries may soon be overwhelmed if cases continue growing at the current pace.

Halladin noted that the Philippines' relatively high death ratio, around 4%, reflects its limited capacity to test and treat patients. As of last Wednesday, the Philippines had checked only 4,700 people. For comparison, Indonesia had tested 11,200 as of Sunday, Malaysia 52,000, South Korea over 460,000, and the U.S. 1.76 million.

The Philippine Medical Association said 17 doctors are among its over 100 fatalities. The government has vowed to step up testing after receiving 100,000 kits from China, which has also pledged to send doctors to help Manila cope.

Vietnam, wary of its own limited ability to carry out mass testing, is urging overseas citizens to rethink plans to return. Nguyen Thanh Phong, chairman of Ho Chi Minh City, warned the city "will lose control" if the number of patients tops 1,000 due to a lack of doctors, hospital beds and ventilators. Responding to the government's call for help, the conglomerate Vingroup on Friday announced it would make ventilators and thermometers.

Malaysia has a relatively developed economy and far higher test count but is stretched thin, too. The government is seeking to recruit doctors, nurses and lab technicians, including retirees. Protective gear is also an issue: Videos shared online show health workers making do with trash can liners, cling wrap and plastic bags. Some companies have donated equipment, while China has sent a few hundred thousand surgical masks.

A woman shields her face with a mask in Hanoi in late March. The crisis has derailed Vietnam's plans as this year's ASEAN chair. © Reuters

A woman shields her face with a mask in Hanoi in late March. The crisis has derailed Vietnam's plans as this year's ASEAN chair. © Reuters As hospitals across the region fill up, some countries are creating makeshift wards. Thailand has decided to convert a university dorm and some hotels. Malaysia did this with an exhibition center and has similar plans for indoor stadiums. Indonesia has opened an apartment block that hosted Asian Games 2018 athletes and is preparing an abandoned island as isolation facilities.

Meanwhile, an uncertain threat looms over nations with even fewer medical resources and porous borders with China -- Myanmar and Laos -- which have logged only a trickle of cases since reporting their first in late March. And at the regional level, the crisis has cast doubt on the raison d'etre of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations itself.

Vietnam, this year's ASEAN chair, postponed the annual spring summit to June, disrupting a tight diplomatic schedule and giving the impression that the bloc is paralyzed in this crisis.

So far, Singapore has been the only one that seemed to have things under control. The city-state took strict virus containment measures early on and boasts an advanced medical system. It has recorded six coronavirus deaths so far, out of about 1,300 cases.

But even the Singaporean government was sufficiently alarmed by rising infections to further restrict economic activity this week -- underscoring the challenges that await its less-wealthy neighbors.