When the clock struck 9 a.m. in Bangkok on Sept. 8, ministers from 16 countries were supposed to sit down to hammer out details of the world's biggest trade deal -- the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership.

Thailand, as the chair of this year's Association of Southeast Asian Nations meetings, was eager to make tangible progress so that an agreement can be signed at the ASEAN Summit in November. But even though there was no time to waste, the meeting was delayed for more than five hours because the attendees were busy doing one thing: persuading India.

"There were some issues that some of the RCEP members, particularly India, did not completely agree to go on, and we needed a few more hours to lobby," a Thai official said.

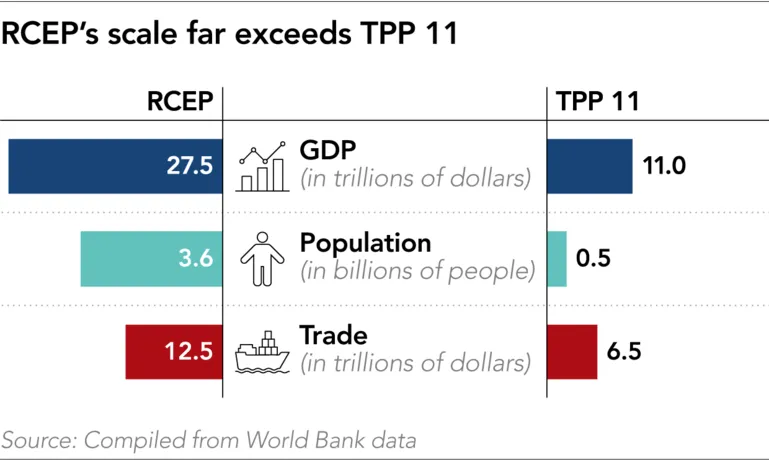

Those extra hours came after years of haggling. The RCEP talks were announced at the ASEAN Summit in 2012 and began in 2013, bringing the Southeast Asian bloc's 10 members to the table with China, Japan, South Korea, India, Australia and New Zealand. Together, they would make up the world's largest free trade partnership, encompassing over 3.5 billion people and about one-third of global gross domestic product -- surpassing the European Union and the North American Free Trade Agreement.

It was slow going early on, but momentum picked up in 2018 as U.S. President Donald Trump waged his tariff war with China and RCEP participants began to see themselves as standard-bearers for free trade.

Yet, the window of opportunity may be closing as quickly as it opened.

Singapore, Japan and other parties had hoped to reach a "substantial conclusion" by the end of 2018. The city-state, last year's ASEAN chair, was especially keen to seal an RCEP deal given its dependence on trade.

India's reluctance to open up its market stood in the way. One participant in a ministerial meeting held last November in Singapore said the Indian delegation cited domestic politics -- the country was headed for general elections in 2019 -- and urged careful wording in the ministers' statement.

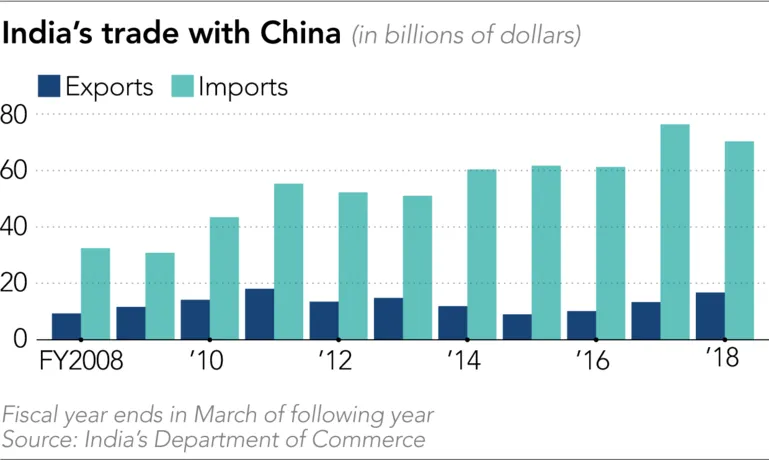

The last thing Prime Minister Narendra Modi wanted to do was alienate farmers, manufacturers and other groups months before the vote. India's trade deficit with China reached about $54 billion for the fiscal year ended March 2019, and lowering tariffs would only bring more Chinese products.

The RCEP participants decided to defer the conclusion of an agreement to 2019.

Since then, Modi won his election handily, but India's stance has not changed much.

India not only runs a trade deficit with China but it believes the deficit "is a result of unfair, restricted market access," External Affairs Minister S. Jaishankar said during a panel discussion at the India-Singapore Business & Innovation Summit on Sept. 9. "So, it's not really comparative advantages playing out, it's actually Chinese protectionist policies which have created that outcome."

Opposition to RCEP tariff elimination is widespread across Indian industry -- iron and steel mills, dairy farms, pharmaceutical companies and textile makers.

Shamshad Khan, a visiting associate fellow at the New Delhi-based Institute of Chinese Studies, suggested India's experience with FTAs in general has been an unhappy one.

"The statistics of bilateral trade with Japan, Malaysia, Singapore, et cetera, with which India has signed FTAs, suggest that the trade balance has grown in partners' favor," Khan, said. "This has created discontent among some domestic circles, [which] have suggested to the Indian government to revisit the FTAs as well as give a pause to the ongoing negotiations of similar [nature]."

He added, "Similar concerns have been raised about the RCEP."

India's resistance has left China deeply frustrated. Beijing went so far as to propose a new trade bloc with only the ASEAN countries plus Japan and South Korea -- basically RCEP minus India and the two Oceanic countries -- but Japan and several Southeast Asian nations rejected the idea.

China, the largest economy in Asia, has reasons to rush. It thinks a deal on the scale of RCEP would show the world which side of the U.S.-China conflict is truly committed to open markets. It also wants to strengthen its economic influence over the region before the U.S.-led concept of a "free and open Indo-Pacific" gains much traction.

But there are no shortcuts, warned Pairat Burapachaisri of the Thai Chamber of Commerce, who has years of experience on the ASEAN Business Council.

"If all members can't reach any conclusion on this issue with India, the RCEP would not reach its goal. And if the RCEP reaches its goal by leaving India behind, the RCEP would mean nothing, as India is a big market that the world cares about," he said.

By 2050, the GDP of all RCEP participants could reach $250 trillion, with China and India accounting for more than 75%, according to a PwC estimate.

China and India, though, are not the only two players butting heads. The widening diplomatic and economic rift between Japan and South Korea, it is feared, could also interrupt the RCEP process.

At a meeting of RCEP trade ministers in Beijing early last month, South Korea's Yoo Myung-hee twice raised Japan's decision to remove her country from its list of trusted trade partners. Hiroshige Seko, Japan's trade minister at the time, called Yoo's move "extremely regrettable" as her assertions "had no connection with the RCEP negotiations."

The clash did not come up in the latest talks in Bangkok, but "it may still be difficult for South Korea to join a deal Japan took the initiative to bring to fruition, as it could spark a backlash domestically," one RCEP-related official said.

Before the Bangkok meeting, Thailand's Commerce Ministry said the negotiations were 70% complete. Afterward, Deputy Prime Minister and Commerce Minister Jurin Laksanavisit would not say how much progress was made -- he only insisted that the countries, including India, were committed to finishing the negotiations by November.

Many diplomats and negotiators say 2019 could be the last chance to get the deal done, at least anytime soon. The ASEAN chairmanship will move on in alphabetical order: Thailand will pass it to Vietnam next year, followed by Brunei and then Cambodia.

These countries, experts say, are less equipped to push things forward than more economically advanced and diplomatically experienced states like Thailand or Singapore.

While there are clearly roadblocks to an agreement, there are also tailwinds -- tailwinds that might never be stronger than they are right now. Thailand, India and Indonesia all had elections this year that kept their incumbents in power. Ostensibly, this should make for smoother talks. If the negotiators fail to strike a deal in 2019, they may rue the missed opportunity.

"I expected they would announce the success of RCEP, saying they have reached an agreement, or at least a framework to liberalize trade and investment," said the Thai chamber's Pairat. "However, there [were] some issues that needed to be put on a sensitive list that need more time to talk."

In Bangkok, the countries agreed to hold high-level meetings in Vietnam's Danang from Sept. 19 to 27. Jurin said another ministerial session would be held before the upcoming ASEAN Summit.

The question is whether these negotiations are a final flurry to work out the remaining nuts and bolts, or a last gasp for a fading dream.