Chuks Ibe is catching up on a backlog of orders in the central London tailor’s shop where he works as an apprentice. Like many, now that national lockdowns imposed during the pandemic are being lifted, he is pondering what the future holds for him and the UK’s capital city.

For now, he and shop owner Paul Kitsaros, who emigrated from Cyprus in the 1960s, have their hands full assisting clients emerging from months of casualwear and tentatively heading back to the office. Yet in the longer term, if some form of working from home becomes the norm, demand for suits could dwindle.

“Everyone has changed and we have to see what the repercussions are,” says Ibe, capturing the prevailing uncertainty in the capital. “The suit hasn’t changed that much. But it might be time for it to develop.”

Though often regarded elsewhere in the UK as privileged, shielded from the worst social and economic shocks, London has by some measures been even more devastated by the pandemic than other parts of the country.

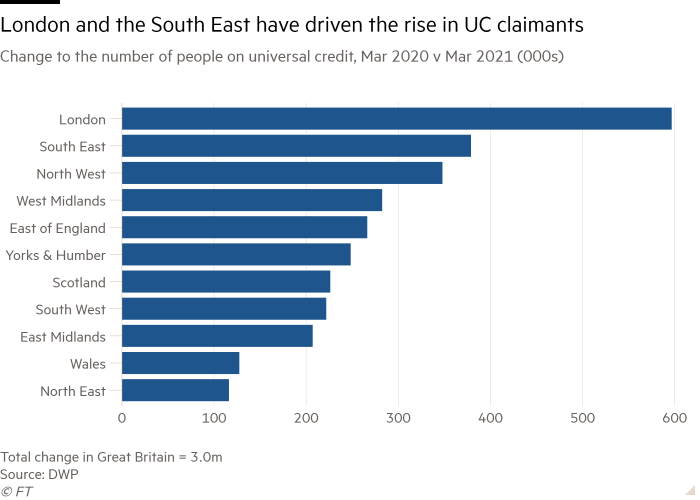

More people have contracted Covid-19 and more have died from the virus in London than any other region; of 127,000 deaths nationally, nearly 15,000 were in the city. More jobs have been lost, with a 5.2 percentage point increase to 8.2 per cent in people claiming unemployment benefits or universal credit. More people have been furloughed too, a total of 710,800 by February — 2 per cent above the national average. Many of those workers could yet join the ranks of the unemployed when the government eventually unwinds its job protection scheme later this year, one of several emergency buffers that have kept things in limbo but that, once withdrawn, could trigger a crisis.

The extent of the damage has raised fundamental questions about London’s future and whether it can recover its 30-year trajectory. Beginning with the financial “big bang” of the mid-1980s, it has grown into one of the world’s foremost global cities, a world centre for finance, law, technology, culture and cuisine that has regularly contributed about a quarter of UK economic output.

Many business owners and residents interviewed for this article put their faith in London’s ability to recover, but wonder whether a return to “business as usual” should even be the aim given how stark pre-pandemic inequalities already were in housing, health and opportunity.

There are also the new realities of Brexit, which arrived under cover of coronavirus on January 1. If a bounceback from Covid is hard enough, tight new strictures governing Britain’s trading and immigration relations with Europe could put paid to the openness underpinning London’s dynamism while limiting the financial sector’s ability to do business with Europe.

During the pandemic there has also been a silent exodus of migrants equal to 8 per cent of the capital’s 10m population, according to the highest estimates, many of them Europeans employed in hospitality or other service industries. The Office for National Statistics disputes this figure, but even if it is only half as much, as the ONS estimates, many businesses are alarmed about a looming labour shortage.

In her book The Nowhere Office, author and entrepreneur Julia Hobsbawm argues that more flexible work patterns risk undermining the agglomeration model that has driven the regeneration of inner London for decades and made mass transport viable. That model has relied on more than 1m people commuting into work and spending money in central areas every day, a pattern now likely to change.

“London is not going to lose its lustre culturally against any other city. But its ability to generate income in the same way is clearly going to be tested,” she says. “It is going to have to reinvent itself.”

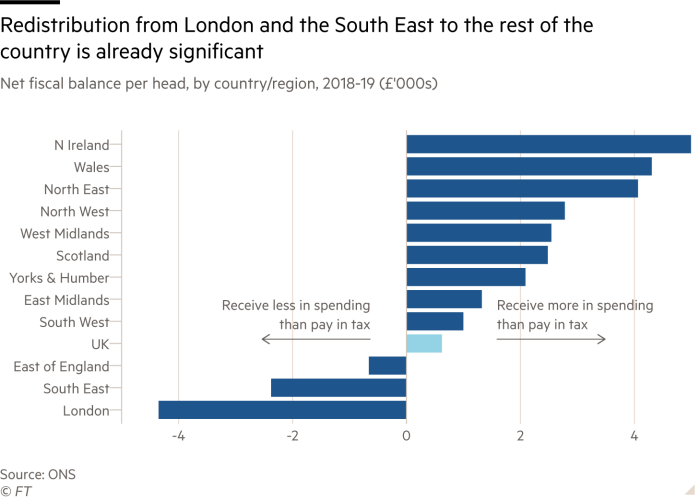

Yet political attention is focused elsewhere. Boris Johnson is seeking to consolidate Conservative party gains at the 2019 general election in former Labour “red wall” strongholds in the north of England. Implicit in the prime minister’s so-called “levelling up” agenda to tackle regional inequality is the suggestion that London has had it too good for too long. Nor is it any more fashionable for the opposition Labour party, which has lost so much ground in the north, to prioritise the capital.

“The next general election will be won or lost in red wall seats,” says a senior Labour politician in London who was not authorised to talk ahead of Thursday’s mayoral election in the capital. “But if we look forward, just recovering is not enough. London will not continue to be a cash cow unless we invest in infrastructure and renewal.”

Return of optimism

Nevertheless, the promise held by the successful rollout of a Covid-19 vaccination programme and the easing of lockdown have combined to bring hope back to the capital’s streets. Central London bars have been filling up outside, after trade resumed on April 12. Restaurants are hiring again and neighbourhoods from Acton in the west to Brixton in the south and Kentish Town in the north are recovering some bustle.

Yet there is still much ground to make up, as the low footfall at Underground stations shows. With the government still advising people to work from home, Bank, a station that serves the City of London, has only recovered to 12 per cent of its pre-pandemic commuter traffic after falling near silent during the tightest months of lockdowns, according to Transport for London.

The viability of Canary Wharf, the high-rise business and financial district developed on old docklands, is at stake, with rail passenger numbers at just 29 per cent of its peak — when 120,000 people worked in the area every day — amid uncertainty about the post-Brexit headcount at big banks that have moved some operations to Europe and elsewhere. Barclays, which has its headquarters in a 32-floor Canary Wharf skyscraper, and other banks have suggested that some employees could continue working remotely even after social distancing measures are relaxed.

And although the central shopping district has inched back to life, it is without tourists to prop-up sales. Underground passenger numbers at Oxford Circus are at 39 per cent of what they were pre-pandemic — 35,422 people daily.

“London’s economy is facing a perfect storm,” says Sadiq Khan, the Labour mayor who goes into elections on Thursday with a lead of more than 20 points over his nearest rival in most opinion polls. “Covid-19 has closed down huge parts of our everyday, consumer economy — last year alone we lost nearly £11bn in tourist spending in central London — while Brexit is no doubt harming our global reputation and competitiveness.”

Poverty was already higher in London before the pandemic than elsewhere in the country, with 2.5m people — or 28 per cent of the population — living in low-income households, compared with 22 per cent in the UK overall, according to official data.

“We need to ensure the recovery brings with it more opportunities for all Londoners ,” says Khan. “We also need to ensure that, as our economy grows, the jobs we create are good and fairly paid.”

![Can London reinvent itself after the pandemic? ảnh 5 Nick Jones of private members club Soho House is optimistic about London’s future. ‘The immense amount of retail space available [in central London] means prices will come down and a whole new wave of creativity will go into those spaces,’ he says](https://www.ft.com/__origami/service/image/v2/images/raw/https%3A%2F%2Fd1e00ek4ebabms.cloudfront.net%2Fproduction%2F49b4ad80-a65a-42a3-95b7-41b58e226aa9.jpg?dpr=1&fit=scale-down&quality=highest&source=next&width=700)

Haringey, a north-east borough of the capital, shows what happens when that is not the case. It combines some of the UK’s wealthiest neighbourhoods, such as Muswell Hill and Highgate, with its poorest — disparities which have only been heightened during the pandemic.

The scale of demand at a food bank run by the Freedom’s Ark church at the old Tottenham town hall is startling. In a pattern seen in many London boroughs, the number of families in need has risen six-fold during the course of the pandemic to 3,000.

“Without this place I would have gone hungry,” says Tunde Adamson, a security guard aged in his 30s who had just completed his training. During lockdown, it proved impossible to find work. “Things are looking a bit more upbeat now,” he says. “But with the exception of a very few industries, people still aren’t hiring.”

Nims Obunge, senior pastor at Freedom’s Ark who is running against Khan as an independent in the mayoral election, says he set up the food bank two years ago because it upset him that children were going without meals in such an outwardly prosperous city. “That can’t be the future of London,” he says.

In the hiatus caused by the pandemic, Londoners like Obunge are trying to envisage how a different city might emerge. The son of a Nigerian diplomat, he would prioritise integrating the many migrants who have arrived over the years. Almost 37 per cent of the city’s population was born outside the UK, according to official figures. “Great opportunity will only be realised when we make all our various communities feel that they have skin in the game,” he says.

Rents and labour

For businesses and residents alike, two issues beyond external factors such as global demand and the evolution of Covid-19 variants will be critical in determining the nature of any recovery. One is property prices and rents. The other is the post-Brexit immigration regime which, for now, is governed by a points-based system introduced in January and designed to favour the highly skilled.

London, prior to the pandemic, was thriving. But it was also dysfunctional. Years of cuts to services and local councils in the name of post-financial crisis austerity had combined with welfare cuts, spiralling rents and an inadequate supply of social housing to tip growing numbers of families into distress.

While the overall population grew by 1.1m to 10m between 2008 and 2017, this was driven by immigration and masked a net outflow of half a million Britons from London to other parts of the UK. Among them were some of those who help any city function — nurses, bus drivers, policemen — many of whom were priced out by high property costs.

“The pandemic has exposed the deep inequalities we knew were there before and have seen play out in our communities for a long time,” says Georgia Gould, chair of the 33-member cross-party grouping of London authorities and Labour leader of Camden borough council.

It has also provided an opportunity for local authorities like hers to take stock, and plan for what comes in Covid’s wake.

Camden, home to the Eurostar rail terminal and the King’s Cross redevelopment around it, where Google is building its vast European headquarters, is releasing land to build new council housing stock.

“We have one of the world’s foremost innovation districts around King’s Cross, but right next to it are some of the poorest communities not just in the UK but in Europe. Some people feel like they are in an island of poverty in between glass,” says Gould. “Our role is to change that, to make sure the value in our communities is shared.”

What next for retail?

A sharp fall in rents, in both the commercial and residential sectors, could aid any rebound, attracting back entrepreneurs, artists and other workers previously priced out of certain London districts.

“The immense amount of retail space available [in central London] means prices will come down and a whole new wave of creativity will go into those spaces,” says Nick Jones, founder and chief executive of Soho House, the private members club group. His company has used the lockdowns to invest in a new space for collaborative working and gyms.

Councils such as Westminster and the City of London, which is creating 1,500 new homes from office space, have also been proactive.

“We have an opportunity in this period of flux,” says Elad Eisenstein, who is running a redevelopment of Oxford Street for Westminster Council and is attempting to reimagine how space might be used in the aftermath of the closure of large outlets such as fashion retailer Topshop and department store Debenhams.

There is also a sense of foreboding. Many businesses — especially restaurants and shops — stopped paying rents during the lockdowns. Should the moratorium imposed by the government on evictions come to an end in June as planned, there is a risk that many of them will not be able to afford to reopen or will end up ploughing their revenue into rent arrears.

“We’re too close to becoming a husk with all the property owned by absentee landlords giving commercial leases to the highest bidder, without any sense of curation or long-term objectives beyond the bottom line,” says Jeremy King, co-creator and owner of some of London’s most famous restaurants, including the Wolseley in St James’s.

He argues that the government needs to step in to trigger wholesale change in the leasehold structure that underpins the city’s commercial property market.

As important for the future of the capital, he says, will be whether the government loosens the post-Brexit rules that limit Europeans eligible to work in Britain to its own definition of the highly skilled. “I think we are at a crisis point. People are now beginning to realise the impact of the new Brexit rules on the workforce,” he says.

Yet despite inevitable bumps ahead, King is not betting against London’s capacity to respond. “The key to London resurging after the pandemic,” he says, “is that we don’t try to revert to how it was before.”