Journalist: - Why do you think now is finally the right time?

Dr. Lê Đạt Chí: - The timing is right because the conditions have matured. Over the past five years, Vietnam’s trade volume has grown rapidly, reaching nearly $800 billion in 2024. At the same time, global trade dynamics are shifting due to geopolitical tensions—especially between the U.S. and China. These changes create a unique opportunity for Vietnam to position itself as a financial and logistical hub.

We’re no longer just a manufacturing outpost. We're now at the center of key supply chains, and it’s time our financial infrastructure reflects that role.

- What exactly are we missing out on without a functioning IFC?

- A lot. Let me give a simple example. A Korean company operating in Vietnam wants to pay for imported goods. Without an IFC here, the company typically processes the transaction through its home bank in Korea, which then settles payments with the exporting country—say, the U.S. or China. So even though the business is happening in Vietnam, the money and service fees bypass us entirely.

That means Vietnam gets no slice of the financial services—no foreign exchange fees, no transaction charges, nothing. All the value is extracted by foreign banks. An IFC would allow those financial flows to remain in-country.

- Can we put a number to this loss?

- Sure. Let’s say we charge a modest 1% fee on trade-related financial services—this includes things like currency exchange and payment processing. With total trade reaching $786 billion in 2024, that’s potentially $7.8 billion in financial revenue. Right now, most of that value leaves Vietnam.

If we had a full-fledged IFC, those billions could stay here—supporting jobs, growing institutions, and reinvesting into our economy.

- You’ve mentioned the “dock and deck” model. Can you explain what that means?

- It’s a concept rooted in real-world logistics and finance. The “dock” represents our seaports—physical infrastructure where goods come in and out. The “deck” is the financial layer, where capital is exchanged, transactions are cleared, and contracts are settled.

This model was how Dubai’s financial center began. When Iran faced sanctions, Dubai stepped in to handle trade and financial transactions on its behalf. Singapore did something similar during the years when Vietnam was under embargo. They managed deals that couldn’t be done directly.

Vietnam now has a similar opportunity: leverage our location, trade ties, and current global tensions to become the middleman—not just in goods, but in money.

- Is Ho Chi Minh City ready to be that financial center?

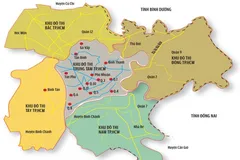

- It’s the only city in Vietnam truly ready. It has the banking infrastructure, talent pool, and international connections needed for this kind of transformation. What’s more, the planned international port in Cần Giờ gives us a rare chance to link logistics with finance directly.

Think about it: ships dock at Cần Giờ, while transactions are cleared at a nearby financial center in HCMC. That’s “dock and deck” in action. We’d be able to offer one-stop services for global trade—cutting costs for businesses and generating revenue for Vietnam.

- Some say we should focus on fintech or green finance. What do you think?

- Those are long-term goals, but they shouldn’t be our starting point. Fintech relies on innovation, startup ecosystems, and intellectual property—all areas where Vietnam is still developing. We don’t yet have enough high-value products or technology to attract serious venture capital.

Green finance is also limited. While global institutions support it, the available capital is still relatively small and spread thin. It won’t sustain a full-scale financial center on its own.

Our immediate priority should be building a traditional, trade-focused IFC that provides real services to real companies. Once that foundation is solid, we can layer on fintech and green finance as we grow.

- What about capital flows? Can we really liberalize foreign capital right now?

- It’s a fair concern. IFCs usually require open capital accounts—meaning money can freely move in and out. But we have to ask: if foreign investors bring capital in, what can they actually buy here?

Right now, Vietnam doesn’t have many large-scale financial instruments. Our bond markets are shallow, our derivatives market is underdeveloped, and there aren’t enough high-quality products to attract serious international investors. So even if we liberalized capital flows tomorrow, there’s not much for that capital to do here.

We need to build those markets first—through government bonds, infrastructure financing, and trade-related securities. Only then does it make sense to open the capital account.

- So we should take a phased approach?

- Exactly. We shouldn’t aim to create a Wall Street or a Singapore overnight. We should build what we’re good at first—supporting trade, managing currency exchange, offering banking services—and gradually grow into more complex financial roles.

If we try to leap too far ahead—focusing on futuristic finance without mastering the basics—we risk building something that looks impressive on paper but lacks substance.

- And what happens if we miss this opportunity?

- Someone else will take it. Thailand, Indonesia, or even Malaysia could move faster. The window is open now because of global trade shifts and political conditions. But it won’t stay open forever.

If we act decisively—by developing infrastructure, aligning regulations, and attracting strategic financial institutions—we can finally turn the vision of an IFC into reality. But if we hesitate, we’ll keep exporting not only goods, but also all the value those goods generate.

- Thank you, Dr. Chí.