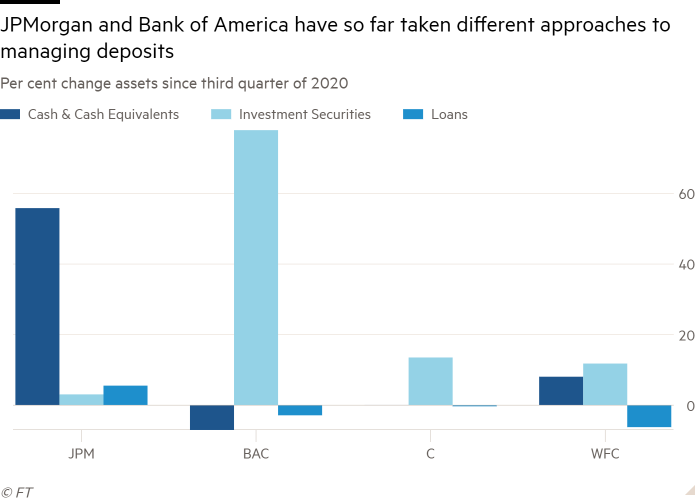

The biggest US banks are pursuing dramatically different strategies for deploying their trillions of dollars of deposits in the government debt markets, highlighting the debate on Wall Street over the direction of interest rates.

On one side is Bank of America, the second-biggest US lender by assets, which helped boost its third-quarter revenues by raking in interest from a debt security portfolio that has grown 77 per cent over the past year and now stands at nearly $970bn.

On the other is JPMorgan Chase, the biggest US bank, which sits on an investment securities portfolio smaller in size and is more inclined to park deposits at the Federal Reserve than squander them on potentially overpriced Treasuries or agency securities.

The divergent strategies added a note of discord to an earnings season in which the leading banks all benefited from a dealmaking boom on Wall Street — and could help determine which lender is more profitable on the other side of the Covid-19 pandemic.

“You’re seeing banks taking various strategies surrounding their balance sheet and interest-rate management,” said Jason Goldberg, bank analyst at Barclays. “Time will tell which is more appropriate than the other.”

The dilemma for the banks is they are struggling to use all the deposits that piled up on their balance sheets as government stimulus and quantitative easing programs were rolled out during the health crisis.

Lending out the money would be their preferred option. But loan growth has been sluggish as companies have found ample liquidity in the bond markets and consumers have paid down debts on credit cards.

Buying Treasuries or mortgage-backed securities provides banks with some yield but carries other risks. If rising inflation leads to higher rates, they would have to mark down the value of bonds in their “available for sale” portfolios and they would miss the opportunity to use their cash for more profitable lending opportunities.

BofA has responded by stepping up its bond buying in the last year, and the move paid off handsomely in the third quarter. Despite a 3 per cent drop in loans, it said on Thursday that net interest income jumped 10 per cent — compared with a 1 per cent increase at JPMorgan and declines of 1 per cent and 5 per cent at Citigroup and Wells Fargo, respectively.

“If banks are struggling to generate loans, that means they’re going to have to absorb more securities,” said Mark Cabana, head of US rate strategy at BofA. “There is expected to be an ongoing, very strong bank bid for Treasuries.”

By contrast, JPMorgan has only increased the size of its debt security portfolio by 3 per cent in the past year. At Citigroup and Wells Fargo, the increase has been 14 and 12 per cent, respectively.

Jamie Dimon, JPMorgan chief executive, has made it clear that he fears Treasury prices could fall. In his April letter to shareholders, he said, “It’s hard to justify the price of US debt.” A few months earlier, he said he “wouldn’t touch [Treasuries] with a 10-foot pole”.

The bank’s chief financial officer, Jeremy Barnum said on Wednesday it was still “happy to be patient” with its excess deposits but was likely to start investing more soon.

Wells Fargo also signalled that it is willing to wait. The bank had started buying more debt securities in the first half of the year, but retreated to the sidelines as rates started to rise. Compared with the second quarter, its investment portfolio held steady.

“Our view now is that there’s more . . . risk to the upside for rates in the near to medium term, and so we think there’ll be better opportunities to deploy as we look forward,” chief financial officer Mike Santomassimo told reporters.

Such caution has been costly in the short run. If JPMorgan and Wells Fargo invested their extra cash at 1.5 per cent they could increase pre-provision earnings by 7 and 5 per cent from what they reported in the quarter, respectively, according to Barclays’ Goldberg.

But if rates move higher, Treasuries could fall out of favour with the banks, creating a negative feedback loop in the markets.

“The risk is as rates rise, their lending businesses look much more attractive and they buy fewer Treasuries,” said Gennadiy Goldberg, senior US rates strategist at TD Securities. “So I think the risk is actually for the Treasury market.”