As orders from Europe and the Middle East dried up due to the coronavirus, Ye Zhenqing knew he would have to take drastic measures to keep his sunglasses manufacturing business from going under. With corporate loans out of reach, Ye pledged his own apartment as collateral for a 2 million yuan personal loan to tide his company over.

"I am extremely cash-strapped right now. It's difficult to apply for a bank loan," said Ye, the founder and CEO of Wenzhou Zhen Qing Eyewear, in the eastern city of Wenzhou. Special low-interest business loans have been introduced to help companies deal with the impact of the coronavirus, but "they don't apply to us," Ye said, adding that small businesses like his have to put up huge amounts of collateral and pay higher interest rates than big companies.

As more businessowners like Ye are forced to pledge their homes to stay afloat, the ramifications for the broader economy could be severe.

Unbanked small businesses form the backbone of China's economy, and they are taking a serious hit from the coronavirus outbreak -- 85% of 1,506 SMEs surveyed in early February expect to run out of cash within three months, according to a report by Tsinghua University and Peking University.

Ye's 2 million yuan loan is enough to cover operating expenses and salaries for about 100 workers for just two months, after which he will need fresh funding or a return of orders.

The coronavirus, which has infected more than 78,000 and killed 2,700 in China, has already shut down large swathes of the economy. A wave of closures or layoffs at SMEs would deal a further blow to President Xi Jinping's efforts to stimulate growth, which economist now expect will fall to just 3% in the first quarter.

Beijing has recognized the cash crunch facing small businesses and deployed hefty financial resources to address it.

Earlier this week, the People's Bank of China earmarked 500 billion yuan in fresh financing to provide cheap loans to smaller enterprises struggling to resume operations amid the coronavirus outbreak. This comes on top of the 300 billion yuan re-lending quota authorized this month by the central bank.

"If the support quotas are not enough, we will increase them further," Liu Guoqiang, vice governor of the PBOC, said at a news conference on Thursday.

The People's Bank of China has earmarked 500 billion yuan to provide cheap loans to small businesses struggling amid the coronavirus outbreak. (Photo by Akira Kodaka)

The People's Bank of China has earmarked 500 billion yuan to provide cheap loans to small businesses struggling amid the coronavirus outbreak. (Photo by Akira Kodaka) But such programs are not trickling down to the businesses that need them, according to Zhang Qinghua, who works at a Guangzhou-based financial services company and helps small businesses apply for loans.

"There is a huge demand for loans right now as most small and medium-sized enterprises will face cash drain within three months," he said. "Most companies are on the fence about whether to continue or not, whether it's worth it to take loans. Some company owners have already chosen to wind up their business."

The existing loan programs, he added, are skewed toward manufacturers of medical supplies or companies in the hardest-hit areas, such as Hubei and Guangdong provinces.

Beijing's attempt to stamp out shadow banking has inadvertently exacerbated the cash crunch. The clampdown was intended to address a systemic risk to the economy, but it also wiped out trillions of yuan in funding previously available to small businesses.

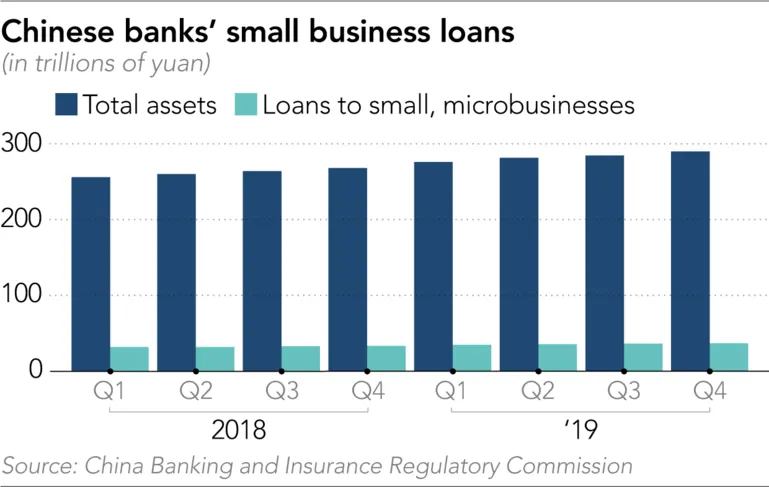

Government efforts to increase access to commercial credit, meanwhile, have borne little fruit. Loans to small and microbusinesses and sole proprietors accounted for 12.7% of all outstanding local and foreign currency assets of Chinese banks, or 36.9 trillion yuan, as of December 2019, little changed from 12.5% a year earlier, data from the regulator shows.

Just over a quarter of the estimated 25 million small businesses operating in China have taken out some form of commercial loan from a bank, according to Hong Kong-based fund manager Value Partners.

"There is clearly room to grow," said Luo Jing, a senior fund manager at Value Partners, which manages $14.2 billion and owns Chinese banks through its various funds. "One of the biggest impending factors is the fact that banks don't have a clear understanding or a reliable data set to judge whether a small company can qualify and then subsequently service the loan. Having said that, over the past two years they are addressing it by investing in technology for data capture and tying up with fintechs for online loan disbursement."

The plight facing a power plant component manufacturer based out of Chengdu epitomizes the difficulty smaller business face in securing bank loans. As the majority of the company's 200 employees have only just returned to work following the Lunar New Year break, it has only been able to resume limited production at its plant. This has led to delayed schedules and eaten into its cash reserves, despite orders continuing to come in.

A member of the company's founding family, who declined to be named, said the company has approached banks seeking low-interest loans. While the banks have not rejected its applications, they verbally informed the company that it will take months for a decision to be made, due to the time needed to scrutinize the application and analyze the company's prospects.

"We expected a sub-5% annual interest rate, but the indication is it will be almost 7% and the collateral value apparently has to be bigger than the loan," the family member said.

"Officials at two banks have also indicated we can pledge a personal property and get a loan faster, but it would be just over half the amount we are seeking."

Funding based on physical collateral alone will not be enough for companies to stay afloat, according to Alicia Garcia Herrero, chief economist for Asia Pacific at Natixis. They need business loans.

"That can only happen through a combination of shadow banking and lending by smaller and regional banks," she said. "Before that the government either needs to recapitalize the smaller banks or get a stronger lender or an asset manager to buy the weaker ones with a caveat they lend to small businesses."

Andrew Collier, managing director of Hong Kong-based Oriental Capital Research and previously and the president of Bank of China International-U.S., also advocates a return of certain forms of shadow banking such as regulated private funds to tide over the crisis. "To a certain degree China should let the genie out of the bottle again and go back to shadow banking," Collier said. "China is clearly unwilling to unleash a massive credit stimulus like the one in 2009 as it doesn't want a banking collapse. So encouraging the growth of private funds is a good option and it has worked before."

Entrepreneurs would likely welcome such moves. Ye, the sunglass manufacturer, is gearing up to reopen his factory on March 2, a full month behind schedule as Wenzhou was put on lockdown amid the outbreak of coronavirus.

He is worried that he might default on the 2 million yuan loan if the epidemic is not brought under control in the next month. "We'll certainly face pressure if business does not get better."