Most high-speed trains have not stopped in Wuhan since Chinese authorities locked down the city on Jan. 23, in an attempt to control the outbreak of the novel coronavirus that originated there. Most, but not all. Some have kept special reserved carriages, occupied by experts heading into the middle of the quarantine zone -- not to its clinics or hospitals, but to Yangtze Memory Technologies, China's most high-profile memory chip project.

"You have to present special permits from both local and central governments, and medical proof that you are healthy when you board the train. You will then be arranged in a special carriage, along with other people who are also returning to work in strategic industries such as semiconductors," a person briefed on the process told the Nikkei Asian Review.

"Yes, don't be surprised. The train will stop at Wuhan for you."

Beginning in February, Yangtze Memory sent cars to the station to pick up groups of staff, depositing them at a self-quarantine dormitory for a week before they were allowed to enter the main working area, sources close to the project told Nikkei.

High-speed trains sit idle at a Wuhan station. The city has, officially at least, been in total lockdown since late January. © Getty Images

High-speed trains sit idle at a Wuhan station. The city has, officially at least, been in total lockdown since late January. © Getty Images These secret trips, which have not yet been reported, brought volunteer employees back to the center of the epidemic to relieve some 300 engineers who had been working on rotating shifts at the factory since the shutdown began. Many were young professionals under the age of 30, who were originally assigned to cover the Lunar New Year but then became stranded at the facility. For more than a month, they labored to keep the plant running.

"They are banned from leaving the company campus and are under massive pressure. ... Most of them work more than 10-12 hours a day and are on call all the time," said an industry source familiar with the matter. The government also lifted labor regulations to allow employees to work more than the mandatory cap of 36 hours overtime a month.

In Hubei Province, where Wuhan is located, schools closed, trains stopped, and malls and supermarkets shut down. But the chipmaker stayed open, enabled by the local and central governments, which gave special dispensations to allow it to bring in materials and labor, and to ship finished goods out of the province to distribution centers in Shanghai. The company portrayed this as a heroic effort, and encouraged employees to submit stories about their efforts during the outbreak to the Chinese Communist Party, according to an internal note obtained by Nikkei, so that "those would later become great historical materials."

Chinese President Xi Jinping visits Wuhan on March 10: His government has made chipmaking a key industrial priority. (Xinhua/Kyodo)

Chinese President Xi Jinping visits Wuhan on March 10: His government has made chipmaking a key industrial priority. (Xinhua/Kyodo) Remarkably, Yangtze Memory was even hiring for positions in engineering, operations, integration, production business development and marketing -- and most of these new openings were based in Wuhan. "We will stay away from the virus, but we will not keep ourselves away from good talent," declared a job advert posted on Feb. 26 and March 3.

That the Chinese government -- which shut off huge swathes of the country's economy to limit the spread of Covid-19 -- was prepared to risk further contagion to keep this factory running shows how committed it has become in its desire to build a powerful domestic chip sector. With high-technology industries increasingly caught up in geopolitical tensions, China is desperate to decouple its companies from their reliance on U.S. imports, and to build homegrown competitors to the American, South Korean and Taiwanese companies that dominate the market. Beijing has thrown billions of dollars at the industry, creating a nascent boom that not even a global pandemic could deflate.

"China's dependence on U.S. and foreign technology is not only an issue of national security," said Alex Capri, a senior fellow at the National University of Singapore Business School and research fellow at the Hinrich Foundation. "It poses a serious impediment to the Chinese Communist Party's geopolitical ambitions as a rising power, as virtually all hard and soft power will depend on achieving technology supremacy.

"A massive industrial policy initiative to develop, promote and protect its own China semiconductor industry is underway. It's not only about market share. It's techno-nationalism at work."

The Big Fund

The Chinese government has long harbored ambitions to build an independent technology supply chain to compete with that of the U.S., but its efforts have gathered pace since 2014. The previous year, former U.S. intelligence contractor Edward Snowden had gone public with a cache of documents revealing the extent of American surveillance programs around the world. That heightened a fear that geopolitical rivalries were going to play out through strategic technologies, and prompted China to re-examine its technological vulnerabilities.

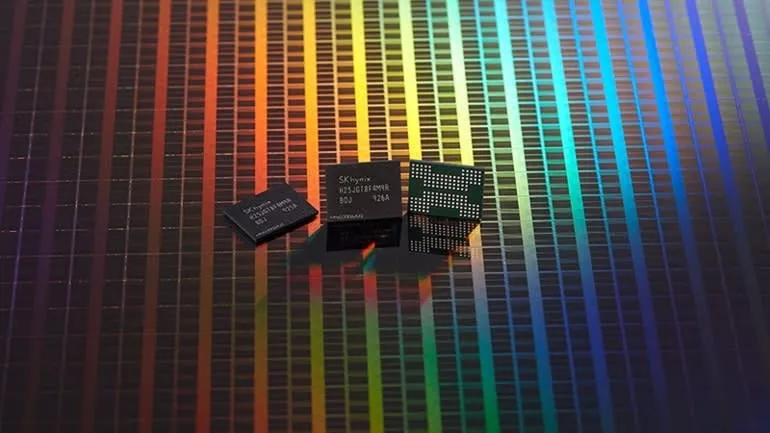

Memory chips came high up the list. Components like NAND flash memory chips are ubiquitous in smartphones, computers and servers, as well as in the next generation of connected cars and "internet of things" devices. Six companies -- Samsung Electronics, Kioxia, SK Hynix, Western Digital, Micron Technology and Intel -- make up nearly 100% of the market. None of them are Chinese, meaning that to compete globally, China's national champions -- Huawei Technologies, ZTE, Xiaomi, Alibaba Group Holding and Lenovo -- rely on imported technology.

Attempts by Chinese companies to gain access to U.S. technology through mergers and acquisitions have been repeatedly thwarted. In 2015, the state-backed tech conglomerate Tsinghua Unigroup tried to buy out Micron and take a stake in Western Digital, but both bids were blocked by the interagency Committee on Foreign Investment in the U.S. due to national security risks. Other Chinese attempts to buy chip-related companies such as Lattice Semiconductor and Aixtron fell apart due to U.S. government intervention. Chipmaker Broadcom's takeover bid of Qualcomm was also called off by the Trump administration over national security reasons in 2018.

Yangtze Memory Technologies' sprawling Wuhan campus, pictured under construction. (Photo courtesy of Tsinghua Unigroup)

Yangtze Memory Technologies' sprawling Wuhan campus, pictured under construction. (Photo courtesy of Tsinghua Unigroup) Tsinghua Unigroup was also derailed in its attempts to acquire technology from Taiwan. In 2016, the company tried to buy Siliconware Precision Industries, Powertech Technology and ChipMOS Technologies -- all leading Taiwanese chip packaging and testing suppliers -- but was blocked by the China-skeptic Tsai Ing-wen government each time.

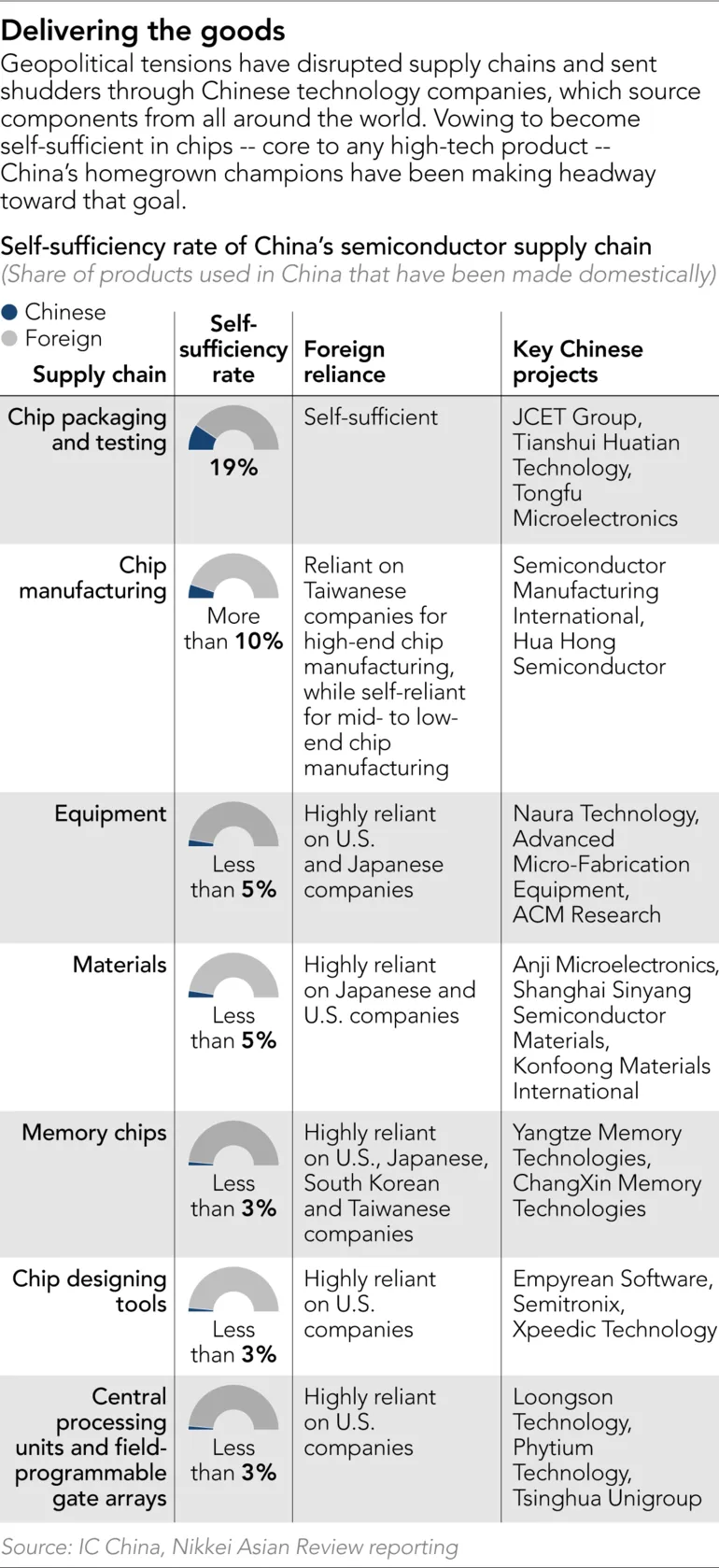

In 2014, Beijing announced the China Integrated Circuit Industry Investment Fund, nicknamed the "Big Fund," a 138.7 billion yuan ($19.8 billion) vehicle to seed the domestic semiconductor industry. The capital was expected to multiply tenfold with other venture funding from local governments and the private sector, and to be further boosted by new tax breaks for manufacturers and buyers who switched from international to domestic components. The ambition was to produce 40% of the semiconductors used by Chinese companies by 2020, and 70% by 2025.

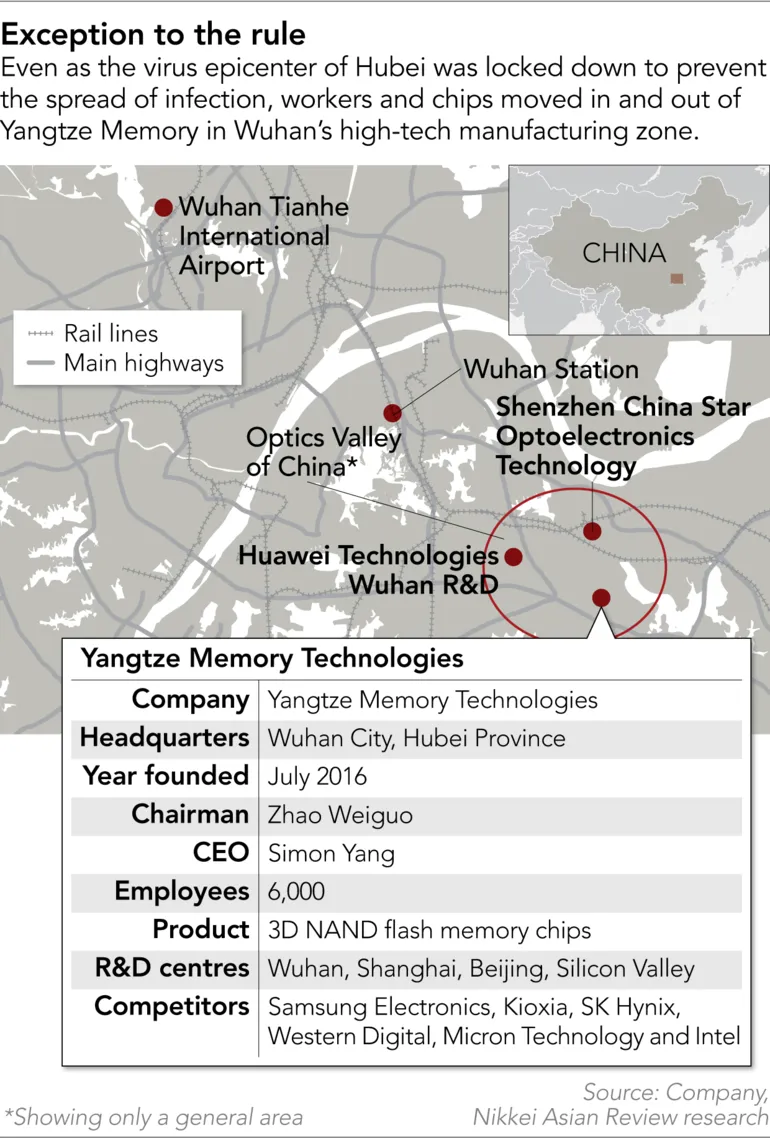

Yangtze Memory is one of the highest-profile projects to emerge under the initiative. Founded in 2016 in Wuhan, it is a $24 billion project backed by Tsinghua Unigroup, Hubei Province and the national Big Fund. It now employs around 6,000 people, and has offices in Shanghai, Beijing and Silicon Valley. The group's campus in eastern Wuhan is the size of over 160 football fields. There, it is building a huge memory chip plant that could, when finished, churn out 300,000 wafers a month, equivalent to more than 20% of global output of NAND flash memory chips.

That would move it past SK Hynix, Micron, and Intel -- in production volume, if not in quality. The company is also working with parent Tsinghua Unigroup at another site in Chengdu, Sichuan Province, which would also be able to produce another 300,000 wafers a month.

"You can certainly feel the government support here. ... Making profits and going public with [initial public offerings] as quickly as possible are not the priority of the project, but building the country's own chips and realizing the Chinese dream are," an industry executive familiar with the project told Nikkei.

Although its technology is still at least one generation behind its international competitors, Yangtze Memory has just begun to produce China's first homemade 64-layer 3D NAND flash memory chips. Chinese companies such as Huawei and Lenovo are among the first wave of buyers. NAND flash memory chips are vital storage components used in electronic devices from smartphones, tablets, PCs, servers and data centers. The layered-3D stack production technology is patented and controlled by foreign players, but Yangtze Memory says it has developed its own stacking structure for building such chips. The company declined to comment for this article.

The scale and speed of its success explains why, despite the risks involved, the government has allowed -- and even encouraged -- its production lines to stay open during the lockdown.

"Yangtze Memory is recognized as one of China's most important semiconductor projects for them to reach self-sufficiency," said Avril Wu, an analyst at data provider TrendForce who tracks Chinese memory chip projects. "The support from policymakers will definitely not change because of the virus."

The company's output may be less than planned this year, Wu said, but its long-term goals will remain. "We do still believe it could become a formidable challenger for many current industry players such as Intel and Micron by the end of 2021."

Samsung, SK Hynix and Micron Technology control more than 95% of the $62 billion market for DRAM, chips crucial to memory retrieval. (Photo courtesy of SK Hynix)

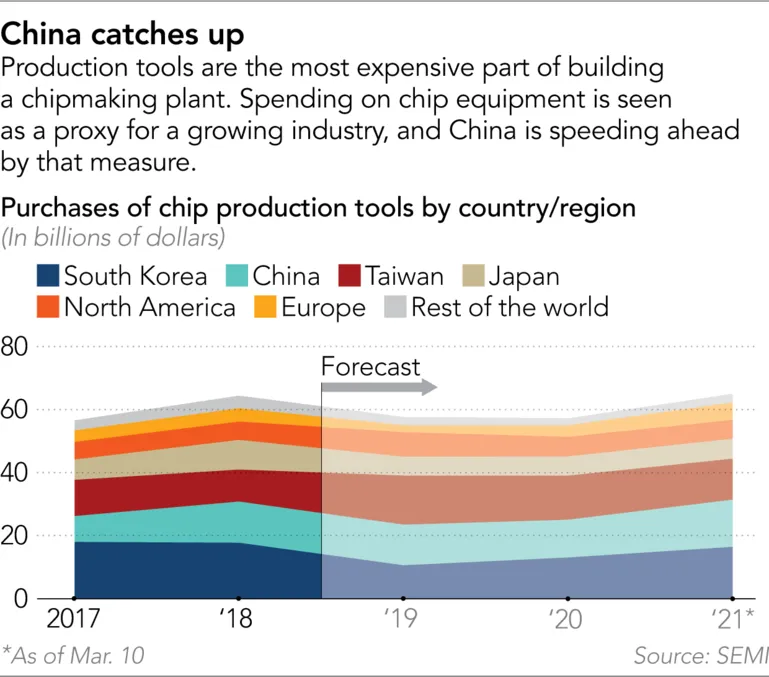

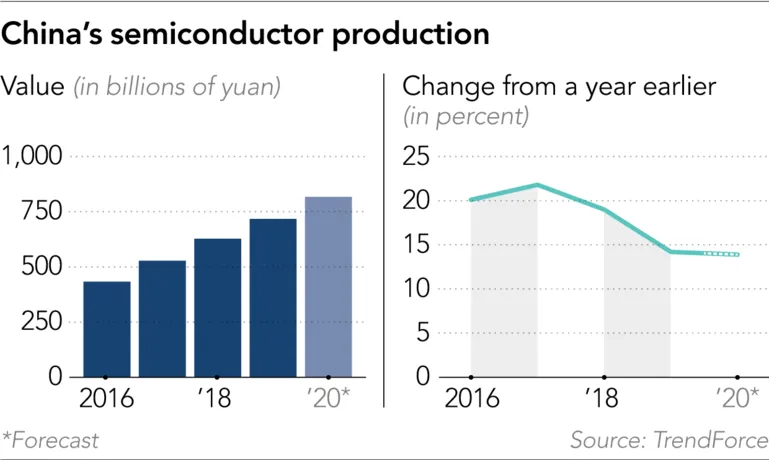

Samsung, SK Hynix and Micron Technology control more than 95% of the $62 billion market for DRAM, chips crucial to memory retrieval. (Photo courtesy of SK Hynix) Although Yangtze Memory is one of the largest and most visible of China's new crop of chipmakers, it is not the only one. The billions of dollars of investment triggered by the Big Fund have created numerous companies whose double-digit growth has become a magnet for talent. In 2019, the global semiconductor industry shrank by 13%, but China's grew by more than 14%, according to research from TrendForce. According to industry association SEMI, from 2017 through 2020, more than 60 new chip plants will go into production globally. More than 40% of those will be in China.

Thousands of people, from early and midcareer professionals through to industry veterans, have joined the gold rush into the Chinese chip industry. The Nikkei reported in 2019 that more than 3,000 professionals from Taiwan had joined the sector in recent years.

Big names from global players have moved to Wuhan. Among them is Chiang Shang-yi, the former co-COO of Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co., the world's biggest contract chipmaker and a key supplier to Apple and Huawei. An industry veteran who led TSMC's research and development team for more than a decade, Chiang last year joined as CEO of little-known chipmaker Hongxin Semiconductor Manufacturing Co., which receives undisclosed funding from the private sector and local government agencies.

The 73-year-old U.S. citizen was motivated by a desire to "[build] his own legacy and to realize a business plan he had always wanted to do," said a source close to Chiang. "Only in China could he find investors willing to pour funds into costly semiconductor projects." Building one advanced chip plant typically requires an investment of at least $10 billion.

Headhunters told Nikkei that Hongxin Semiconductor is trying to hire the best talent in the industry and is willing to pay for it. Director-level managers are being offered salaries as high as $300,000 per year -- more than the remuneration of equivalent positions at Apple, Qualcomm and Intel, a headhunter familiar with the matter said.

Hongxin Semiconductor is currently building a semiconductor plant for advanced 14-nanometer chips and is set to enter mass production by 2022, sources briefed on the plan said. Later, it will even develop advanced 7-nm chips, promises the company's website. The smaller the size of the chip, the more advanced, challenging and expensive it is to produce. The 14-nm chips are roughly two generations behind what industry leaders TSMC and Samsung are capable of making now but are advanced for a Chinese manufacturer.

Chiang was on a trip to talk to ASML, Europe's biggest semiconductor equipment supplier, about future procurement when he learned the news that government authorities had decided to lock down Wuhan, sources told Nikkei.

Others have also been able to hire leading industry figures. ChangXin Memory Technologies, which is building an $8 billion dynamic random access memory, or DRAM, project in the eastern city of Hefei, now has 3,000 employees, with many drawn from Siemens, Micron, Samsung, Infineon and other big names. Karl Heinz Kuesters and Peter Poechmueller, two former executives from Qimonda of Germany -- once the world's second largest memory chipmaker -- are acting as technology advisers, sources close to the project said.

The Chinese company is working to break the dominance of Samsung, SK Hynix and Micron, who control more than 95% of the $62 billion DRAM market. DRAM, similar to NAND flash, is also a type of crucial memory chip, widely used in electronic devices to help quickly retrieve and access data.

A huge display at a Beijing shopping center shows a state television broadcast of Xi's visit to Wuhan. © Reuters

A huge display at a Beijing shopping center shows a state television broadcast of Xi's visit to Wuhan. © Reuters Tsinghua Unigroup last year hired Yukio Sakamoto, the former CEO of Japanese DRAM maker Elpida Memory, to help start a memory project in Chongqing, aiming to begin mass production in 2023. Charles Kao -- former president of Nanya Technology, the world's fourth-largest DRAM maker and the godfather of Taiwan's DRAM industry -- joined Tsinghua Unigroup in 2015 to help lay the groundwork for Yangtze Memory. Along with Sakamoto, he is now working on the new DRAM project in Chongqing.

Big Fund-backed Semiconductor Manufacturing International Co., China's top contract chipmaker and smaller rival to TSMC, has been secretly recruiting a new business development and marketing team in Shanghai and the U.S. to promote its latest technology, sources told Nikkei. SMIC's co-CEO is Liang Mong-song, an industry heavyweight formerly of TSMC and Samsung. The company is close to producing China's first 14-nm chips and hopes to break into the lucrative market of building customized chips for major technology companies.

"The team is to help SMIC promote its new advanced technology platform and expand its customer base, as previously the company didn't have such production technology," a source familiar with the recruiting plan said. SMIC has nearly doubled its capital spending to $3.1 billion for 2020, despite the threat of the coronavirus.

The money washing around China's chipmakers has made it irresistible for many in the industry.

"I had never thought that, in this era, working in the semiconductor industry could be so valuable. ... But the only way to quickly more than double your current salary is to look for emerging Chinese players," said a chip industry manager from Taiwan who went to work in China last year. "I am not worried that Chinese chip companies are only willing to sign a two- to three-year contract with me and later I might have to find another job. ... Given the boom of the sector in the country, I feel like I don't need to worry about my career for the next 10 years."

A sanitation worker sits in the deserted area around Wuhan's closed Hankou Railway Station. © Reuters

A sanitation worker sits in the deserted area around Wuhan's closed Hankou Railway Station. © Reuters Headwinds

For all its investment, China's chip industry still has a lot of catching up to do. Most manufacturers remain behind their international rivals in quality, and the ramp-up in volume is behind schedule. Chinese-owned chip production can currently only fulfill 4.2% of the local chip market, according to data from IC Insights.

The industry is also facing strong headwinds. As the tech war with the U.S. accelerated, more U.S. exporters were unable to gain permits and were forced to stop shipments to some Chinese companies such as Huawei and Hikvision. Beijing quickly made another 204 billion yuan available for the industry, in the so-called Phase Two of the national Big Fund.

The U.S. government has specifically targeted chipmakers. At the end of 2018, U.S. companies were barred from dealing with Fujian Jinhua Integrated Circuit Co, a nascent Chinese DRAM chip program, citing industrial espionage.

Perhaps most damaging are limitations on the export of chipmaking machinery from the U.S. to China. In November, Nikkei reported that the U.S. has even pressured the European chip equipment maker ASML to suspend a cutting-edge tool shipment to Beijing-backed SMIC.

"A potential U.S. move to further restrict China's uses of advanced chip production tools is even concerning. ... The country currently could not immediately get around those crucial chip equipment [restrictions] to build its own cutting-edge chips," Roger Sheng, the lead semiconductor analyst with Gartner, told Nikkei.

The coronavirus will also inevitably have an impact. Over the past few years, Wuhan has emerged as one of the major hubs for the industry. The outbreak and the city's near-total shutdown for 50 days and counting will create delays to projects and make it harder to hire staff.

Added to that is the virus's likely impact on the wider Chinese economy. Set to grow at 5% in 2020, according to ratings agency Standard & Poor's, it will be the slowest rate in decades and have spillover effects for all sectors.

On March 4, President Xi Jinping told China's top policymaking panel, the Politburo Standing Committee, that the government would accelerate investments in "new infrastructure," such as fifth-generation networks and data centers, to enable the development of high-tech sectors, including artificial intelligence, augmented reality and autonomous vehicles. While that would be a boon for makers of chips, the fundamental core of those technologies, it may not be enough to prevent a shakeout; local governments, which are often co-sponsors of projects, will be under pressure to juggle resources to support other sectors hit by the coronavirus.

"At the end of the day, if China later suffers a major economic slowdown brought on by the coronavirus outbreak, we are not sure if all these local governments could still be that committed, and have all the money to sponsor all the chip projects they previously promised -- especially some smaller ones," said Sean Yang, an analyst at Shanghai-based CINNO.

"Of course, we are not worried about those top chip projects like Yangtze Memory," said a chip industry executive. "But it's likely there will be consolidations of smaller projects going on, and casualties after the epidemic. It will not be like in the past few years, where people just presented a business plan about semiconductors and many local governments would buy that idea."

In recovery

On March 10, Xi unexpectedly visited Wuhan -- the very first time since the city was locked down -- sending a signal that its reopening is in sight.

The Hubei provincial government said it would divide the region into low-, middle- and high-risk areas to gradually allow enterprises to restart work and production. Most companies in Wuhan will not be allowed to resume work before March 20, apart from the medical suppliers and the chip and electronics-makers that have stayed open through the lockdown.

A ceremony for the closure of Wuhan's last temporary hospital. Workers hold placards reading: "Victory of the country, victory of Hubei, victory of Wuhan." © Reuters

A ceremony for the closure of Wuhan's last temporary hospital. Workers hold placards reading: "Victory of the country, victory of Hubei, victory of Wuhan." © Reuters "The epidemic will bring short-term economic and social impacts on Hubei, but it will not affect the positive fundamentals of its economics in the longer term," Xi said in a press statement during his Wuhan visit. "The central and national agencies should continue to enhance support for Hubei, helping the province to solve difficulties so it can return to the right track soon."

After Xi's visit, Yangtze Memory immediately set a goal to bring almost all employees back to work by the end of this month, regardless of whether Wuhan has been officially reopened, sources told Nikkei. The company also launched a special campaign offering two coronavirus tests per person -- which would ensure that returning staff were healthy, and significantly shorten employees' quarantine period and encourage them to return to the workplace sooner, a source with knowledge of the situation told Nikkei. Two days after Xi's visit to Wuhan, the Phase Two Big Fund approved an undisclosed investment into Yangtze Memory. The new capital injection will focus on quickly increasing the memory chip maker's production capability and helping launch Yangtze Memory's second-phase production project.

"It's the strategic industry, so everything moves faster than other industries. ...The company has just canceled the daily meal allowance for those who work remotely to prompt employees to return to the workplace," a source told Nikkei. "But if you are on site, the company will grant double overtime pay."

Many workers are likely to heed the call. "Most of the local colleagues who are already on site are quite patriotic," another source with knowledge of the situation said. "They think they are part of a team helping the company and the country to prove to the world that they can survive this critical virus battle."