Scientists and researchers are racing to find treatments and a vaccine for the new coronavirus, as confirmed cases around the world soared past the one million mark and deaths topped 50,000. Meanwhile, governments have been taking even stricter measures to keep people at home and avoid crowded areas.

Here are seven things to know about the medical and health aspects of the coronavirus, formally known as severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2, or SARS-CoV-2, which causes the COVID-19 illness.

What are the symptoms, and what is the fatality rate?

People who have contracted the virus mostly develop upper respiratory illnesses, including a fever, a dry cough and fatigue. While many symptoms of COVID-19 appear similar to that of the common flu, some patients display more severe symptoms such as nausea, a shortness of breath, as well as persistent pain and pressure in the chest. Recent studies by researchers at Harvard Medical School also found that the loss of smell or taste could be an early sign of infection as the virus is capable of attacking key cells in the nose. Experts also say that patients showing symptoms of pneumonia need to be tested quickly.

The fatality rate of COVID-19 is about 4.9% globally as of April 1, according to the World Health Organization. That compares to a death rate of about 9.6% for severe acute respiratory syndrome, or SARS, and over one third for Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS). However, the COVID-19 figure is based on the cumulative number of deaths among confirmed cases, while many infected people with mild or no symptoms are absent from the data unless they are tested. Death rates tend to be much lower in countries with high testing rates.

Are certain groups of people more likely to become infected?

In general, older people and people with preexisting medical conditions, such as high blood pressure, heart disease, cancer and diabetes, are most at risk of serious illness. A recent study published in the medical journal The Lancet -- tracking more than 70,000 COVID-19 patients in China -- shows that more than 8% of patients from the ages of 50 to 59 became severe cases, almost double that of the 40- to 49-year-old age group.

The number jumps to 16% for those 70 to 79 years old. Still, it does not mean that younger people are unaffected. About one-fifth of patients who died in South Korea were younger than 60, and 12% of the intensive-care patients in the U.S. were aged 20 to 44, according to official figures.

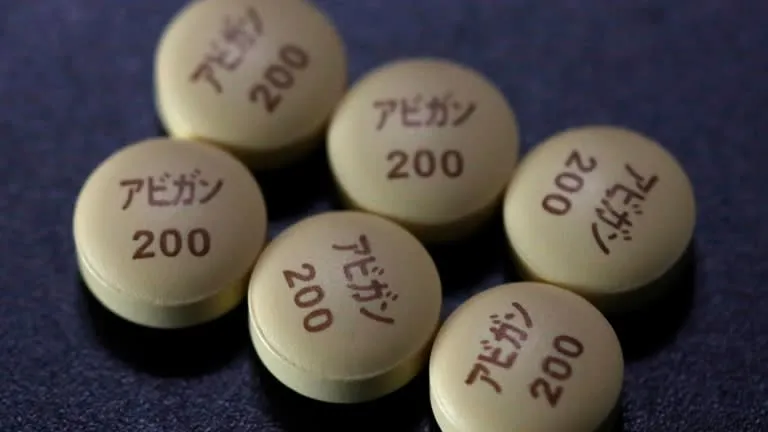

Tablets of Avigan, developed by a unit of Fujifilm Holdings and approved as an anti-influenza drug in Japan. A Chinese government-affiliated institution said it has confirmed the efficacy of Avigan against coronavirus infection in clinical trials. © Reuters

Tablets of Avigan, developed by a unit of Fujifilm Holdings and approved as an anti-influenza drug in Japan. A Chinese government-affiliated institution said it has confirmed the efficacy of Avigan against coronavirus infection in clinical trials. © Reuters What treatments and drugs are being developed, and how close are we to a vaccine?

Scientists are seeking to repurpose existing medications that were made for other illnesses to treat coronavirus patients. Drugs and vaccines being tested for COVID-19 will likely take more than a year to be developed, even as governments around the world fast-track approval processes. "For vaccines, we are looking at mid-2021, the soonest," said David Hui, a professor of respiratory medicine at the Chinese University of Hong Kong. "There needs to be rounds of clinical trials to ensure the treatments are effective and safe to use."

The WHO has launched global trials of four potential treatments for COVID-19: the Ebola drug remdesivir, malaria medications chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine, a combination of HIV drugs Lopinavir and Ritonavir, as well as a combination of those drugs plus interferon-beta.

Separately, Fujifilm Holdings announced the start of a clinical trial for its flu-fighting drug Avigan, which China says was effective in treating coronavirus patients in early trials. Clinical tests are underway internationally to generate more data on the drug's efficacy, which varies by patients' ethnicity.

How useful are masks?

In a word, very. Much discussion has taken place in recent weeks over whether governments should encourage the use of masks. In an article published on Friday in Nature, the British medical journal, researchers said that results from a study "indicate that surgical face masks could prevent transmission of human coronaviruses and influenza viruses from symptomatic individuals."

In Western countries, masks generally had been shunned by the public and carry the stigma of sickness. Both the WHO and the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention had said masks were unnecessary for healthy people, but the CDC is now recommending that everyone in the country wear them. There have been a shortage of masks for medical workers in the U.S., so health officials are urging the use of bandannas, scarves or other fabrics to cover the face.

In Asia, masks are widely used as a way to both lower the chances of getting infected, and to possibly avoid spreading the virus among people who have it but are asymptomatic. Scientists say that masks should be part of a regimen that includes regular hand-washing and hand sanitizers. "Wearing a mask itself is a sign of civility in Hong Kong," Yuen Kwok-yung, a professor in infectious diseases at the University of Hong Kong, said this week in a streaming broadcast. "It deters us and reminds us not to touch our eyes, nose and face."

A medical worker in protective suit inspects a CT scan image at a ward of Wuhan Red Cross Hospital in the Chinese city of Wuhan, the epicenter of the novel coronavirus outbreak. © Reuters

A medical worker in protective suit inspects a CT scan image at a ward of Wuhan Red Cross Hospital in the Chinese city of Wuhan, the epicenter of the novel coronavirus outbreak. © Reuters Is the virus mutating as it travels around the globe?

Scientists say that while the coronavirus has been mutating -- at least two different strains have been found in various parts of the world -- it is likely not as threatening as it sounds because mutation is relatively common. "In the literal sense of 'is it changing genetically,' the answer is absolutely yes," Marc Lipsitch, an infectious disease epidemiologist at Harvard University, told National Public Radio in the U.S.

Lipsitch said in the interview that the issue is "whether there's been any change that's important to the course of disease or the transmissibility or other things" that would be of concern to people. "There is no credible evidence of a change in the biology of the virus either for better or for worse."

Is a person immune to the coronavirus after becoming infected and then recovering?

The short answer is yes, according to the Chinese University of Hong Kong's Hui, but the duration of the immunity is still unclear. "Like many other diseases, patients' bodies will produce antibodies after recovery to prevent them from becoming infected again," he said. "But since COVID-19 is so new, we do not know how long the antibodies will stay."

The antibodies for SARS can last more than three years, while those of MERS remain protective for 10 to 12 months. "This is certainly something that we scientists are watching closely now," Hui said.

Is the virus airborne?

New studies suggest that in addition to droplets from a sneeze or a cough, the coronavirus can be contracted through airborne transmission in certain circumstances including during medical procedures that generate aerosols. The virus can hover in the air for an extended period like an aerosol spray. The chair of the Standing Committee on Emerging Infectious Diseases and 21st Century Health Threats in the U.S. sent a letter to the White House this week, saying: "Currently available research supports the possibility that SARS-CoV-2 could be spread via bioaerosols generated directly by patients' exhalation."

While "specific research is limited," the letter said, "the results of available studies are consistent with aerosolization of virus from normal breathing." Such findings, while still early, are likely to encourage the use of surgical masks, the closure of restaurants, bars and businesses, stay-at-home orders, and other steps to reduce interaction among the public.

Meanwhile, the Nature article said that researchers' results show that "aerosol transmission is a potential mode of transmission for coronaviruses," as well as other viruses.