Global efforts

Governments around the world are taking strong actions to counter the drastic effects of the Covid-19 pandemic, and results show that financial and monetary policies raised GDP by 10% globally. However, the United Nations evaluates that these stimulant measures may not increase consumption or investments as expected.

This situation is explained best by the British economist John Maynard Keynes, who during the Great Depression in the 1930s advocated increased government expenditure and lower taxes to stimulate demand and pull the global economy out of the depression. Keynes suggestion was to avoid a liquidity trap in which interest rates are very low but savings are high, rendering monetary policies ineffective. Consequently, investments do not grow and it is impossible to stimulate aggregate demand.

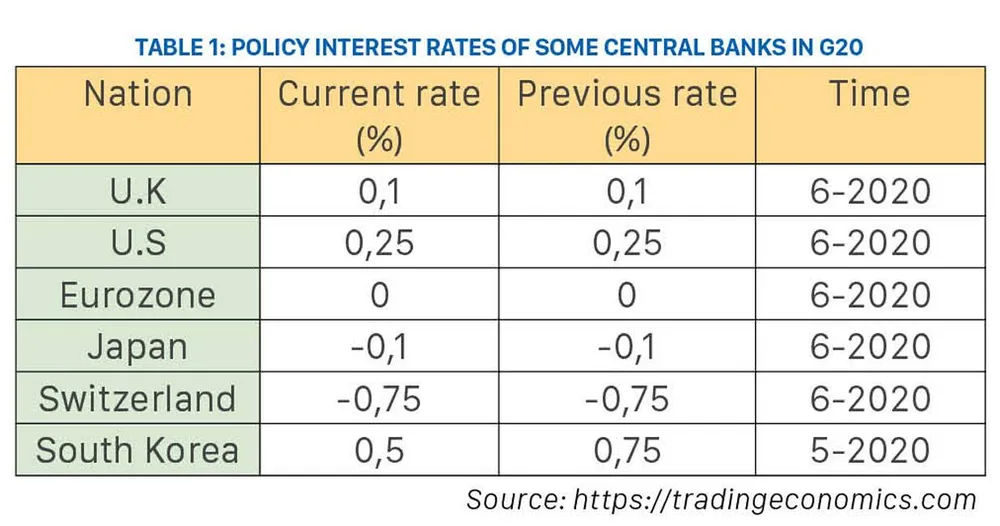

Nobel-Prize winning economist Paul Krugman explains the liquidity trap is no longer contained in the developed countries, but has now spread to developing countries and emerging markets as well. Apart from the US, Europe and Japan, other developed economies are now facing the liquidity trap. Interest rates in these countries have fallen sharply, with 0% in the EU and 0.1% in Japan, while economic growth is still slow (see Fig.1).

Before the outbreak of the Covid-19 pandemic, the policy interest rate was below 5% in developing countries like Peru, Chile, Brazil and Columbia. By June 2020, the interest rates in these countries ranged from 0.25% in Peru to 3.25% in Columbia. Similar results are being seen in emerging markets in Asia and Eastern Europe.

As uncertainty grows by the day, households and businesses will strongly continue to hold onto cash savings. Most of the relief money received from stimulus programs is in bank accounts and banks are facing a liquidity surplus because they cannot provide loans to clients who fail to meet certain requirements or provide a credible collateral.

Since February until April of this year, excess reserves in Banks rose from USD 1,500 bn to USD 2,900 bn, much higher than the USD 1,000 bn level that was during the Great Depression. Enormous increase in bank reserves has shown that economic stimulus policies produce low performance and bank credits cannot cope with this pressure across the globe.

Robust efforts in Vietnam

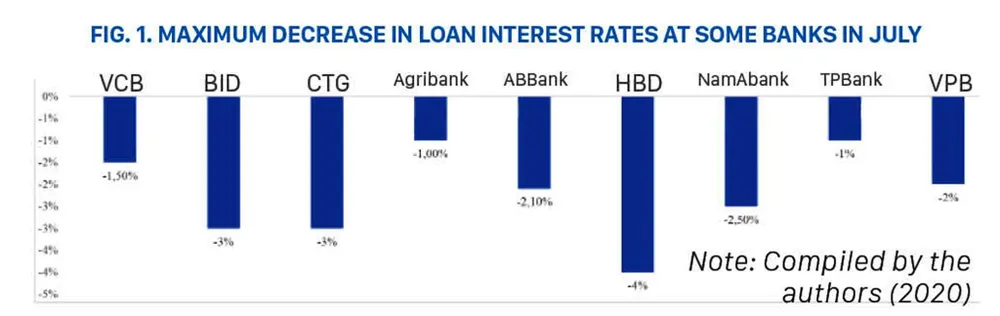

Since the beginning of the year, the State Bank of Vietnam has twice reduced operating loan interest rates, with a decrease of 1.0% to 1.5% per year, in an attempt to promote liquidity in credit institutions. There is also a decrease in interest rate ceilings by 0.6% to 0.75% per year on deposits maturing in less than six months, and the interest rate ceiling has been reduced by 1% per year on short-term loans for businesses receiving preferential support, currently at 5% per year.

Circular 01/2020/TT-NHNN allows banks to restructure the period of debts, reduce or exempt interest rates and fees, and keep groups of debts unchanged so as to provide support for customers hit by the pandemic. These policies enable banks to cut loan interest rates significantly.

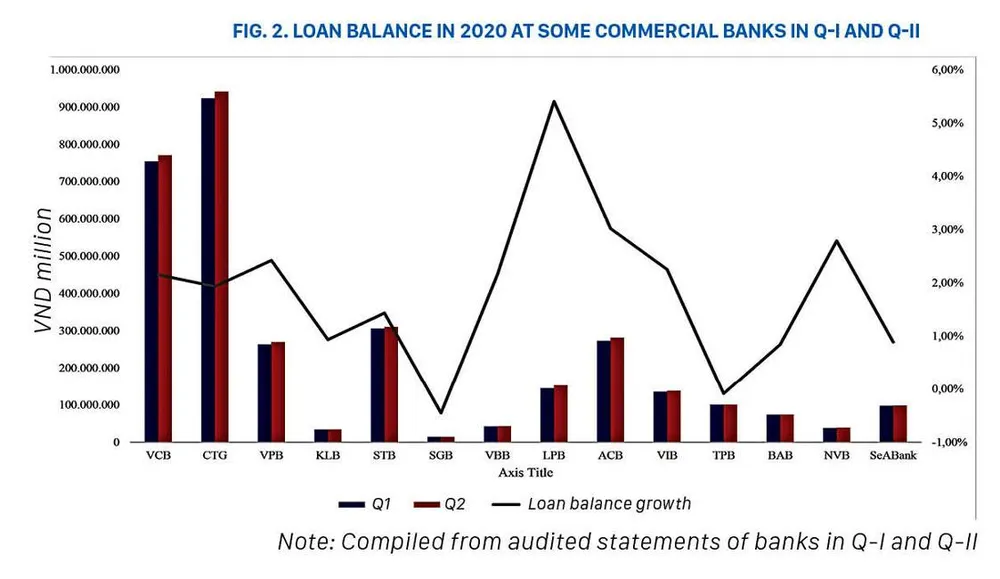

Data received from the General Statistics Office of Vietnam indicates that credit growth in the entire economy in the first six months of 2020 reached 2.45%, lower than 6.22% in 2019 and 7.82% in 2018. This is the lowest credit growth rate seen in last several years despite receiving support from banks. On the other hand, the capital increased by 4.35% in the first half of 2020, almost twice as much as the credit growth rate.

Financial statements released in the second quarter of 2020 show that the loan balance in some banks recorded insignificant improvement, with two out of 14 banks reporting negative growth, namely, Saigonbank and TPBank. Banks have also been unable to increase loans, so they have turned to holding corporate bonds (CBs) and government bonds (GBs). For instance, VPBank has bonds upto 18.9% of its total assets, with CBs rising almost twice as much and GBs going up by 9.6%. This situation has posed a question as to whether Vietnam may have fallen into a liquidity trap same as some other countries.

There are two main reasons that have led to a fall in credit growth. First, companies are hesitating over whether or not to take out loans because of a slowdown in business and manufacturing activities. Talentnet survey in 2020 shows that only 12% of companies have seen growth since 2019. These companies are mostly in the healthcare and consumer sectors, while other businesses have reported significantly lower sales.

Second, loan requirements at banks have now become far too rigid and stringent for small and medium-sized enterprises, as well as household businesses, who are currently the most vulnerable and the hardest hit by the Covid-19 pandemic. For example, four state-owned commercial banks have always offered the lowest interest rate loans in the market. To access loans, companies must have a sound credit history and submit good projects while pledging a reliable collateral or by being a credible long-term client. These requirements therefore make it extremely difficult for small and medium-sized enterprises and household businesses to access loans they badly need.

Impending liquidity trap

There may be some signs of an impending liquidity trap, though this is not yet evident if Vietnam is headed that way, as credit demand still exists even though growth rate has been lower than in last few years. However, it can be inferred that when credit supply fails to boost borrowings, bank capital may be used for financial speculation. Such speculation may increase uncertainty, and this will then discourage consumer spending and investment.

In addition, the Government could issue consumer vouchers to stimulate spending among citizens for a certain period of time through electronic coupons, same as being done in China. This scheme has had a positive effect on consumer spending and on short-term aggregate demand, for all goods and services at this point in time.