From the beginning, the coronavirus pandemic inflicted deeper economic scars on Europe than the US. Now their responses to the crisis mean the transatlantic economies are about to drift further apart.

The EU’s “output gap” — the shortfall in what the bloc was producing compared with its full potential at the start of this year — was double the equivalent differential in the US, meaning the European economy was creating fewer jobs, yielding weaker demand and generating lower inflation.

America will pull further ahead this year, while Europe is held back by less ambitious public spending, tighter restrictions on businesses and a slower rate of vaccinations, economists say.

“The US is now likely to catch up with its pre-pandemic forecast path of growth next year, while if you look at Europe, there is no realistic chance of that happening for several years,” said Erik Nielsen, chief economist at the Italian bank UniCredit.

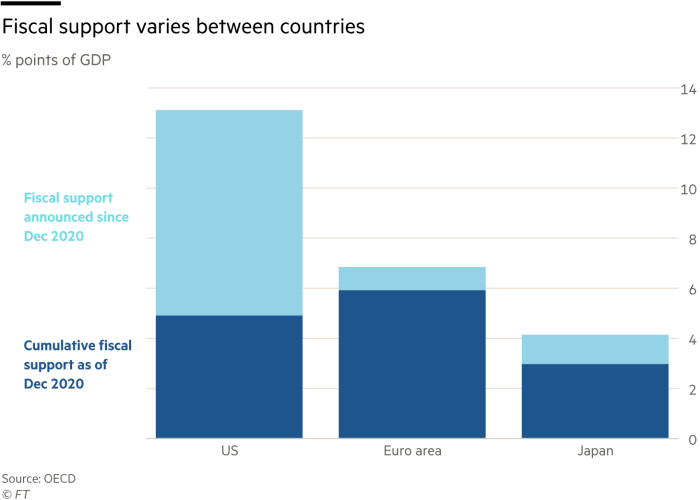

After the US government approved a $1.9tn spending package last week, Nielsen calculated that its economy would benefit from an overall cash fiscal stimulus worth 11-12 per cent of gross domestic product this year — three times the size of its estimated output gap.

In contrast, new fiscal measures planned by the 19 eurozone countries, combined with extra spending on existing welfare schemes, lost tax income and payments from the EU’s €750bn recovery fund all add up to 6 per cent of GDP — 70 per cent of the bloc’s output gap.

President Joe Biden said last week that every US adult would be eligible for a coronavirus vaccination by May 1, as he set the July 4 Independence Day holiday as a target for a return to some normality.

In contrast, the EU is struggling to meet its target of inoculating 70 per cent of adults by September, hampered by production delays and concerns about the effectiveness and potential side effects of the AstraZeneca jab.

Some big US states, such as Florida and Texas, have lifted most coronavirus restrictions, while partial lockdowns were tightened in parts of Europe, such as Italy, after infections rose again.

“The vaccination delays and the insufficient fiscal policy will impact growth in the coming quarters,” said Vítor Constâncio, former vice-president of the European Central Bank. “Europe risks having this year half of the growth rate that the US will achieve.”

The transatlantic decoupling is likely to come to light this week when Federal Reserve officials upgrade their projections for US economic growth for this year. In December, the Fed said it expected median output to increase 4.2 per cent, but on the back of Biden’s $1.9tn fiscal stimulus and a swifter-than-expected vaccination rollout, many predict a faster rebound.

Christine Lagarde, president of the ECB, said last week there was “a time lag” between the US and European fiscal stimulus plans, adding: “Our own fiscal measures are not kicking in yet. And we need that.”

The eurozone economy shrank 6.6 per cent last year — compared with a decline of 3.5 per cent in the US economy — and the bloc is expected to slide into a double-dip recession with a second consecutive quarter of negative growth in the first three months of this year.

The OECD last week forecast that the US economy would grow 6.5 per cent this year and 4 per cent next year, outstripping the eurozone’s predicted 3.9 per cent growth this year and 3.8 per cent forecast for next year.

Lucrezia Reichlin, an economics professor at the London Business School, said EU government officials were showing little appetite to match the US government’s $1.9tn stimulus. Instead, she said, officials were focused on finalising the EU’s €750bn recovery fund that will provide a mix of loans and grants to member states over five years — even if its disbursements will only amount to 1 per cent of the bloc’s GDP this year.

“It cost a lot of political capital to put together the EU recovery plan, so I don’t see them doing more,” Reichlin said. “The discussion is now in France and Italy about whether it is time to discontinue the exceptional measures introduced last year, like the furlough schemes.”

The EU announced this month that its fiscal rules — requiring countries to meet debt and deficit reduction targets — would be suspended for another year in 2022. But Reichlin said their eventual reintroduction, even in a looser form, was a factor holding governments back from loosening the purse strings further.

“Expectations matter,” she said. “The finance ministers know that sooner or later they are going to get hit by the rules again, which is why they are so prudent.”

One idea would be to exclude the €350bn of loans in the EU recovery package from national debt calculations, Constâncio suggests.

Olivier Blanchard, the IMF’s former chief economist, also foresees the “need for more push” from European fiscal measures: “It will depend on the behaviour of private demand, of optimism [and] of the end of precautionary saving.”

However, the US can also count on a bigger potential boost from excess savings, which might swell further when most Americans receive a $1,400 cheque as part of the Biden stimulus.

US households built up excess savings equal to more than 14 per cent of nominal private consumption last year, according to the OECD. Meanwhile, French, Spanish, Italian and German households accumulated extra savings equal to between 3 per cent and 7 per cent of consumption.

“The balance of risks are tilted towards an even greater decoupling over the coming year thanks to excess savings,” said Richard Barwell, head of macro research at BNP Paribas Asset Management. “There is more spare firepower sitting on household balance sheets in the US and more chance that it will be spent if animal spirits surge as the economy comes roaring back.”

Another rift could emerge — in monetary policy. The Fed is unlikely to signal any imminent shift after setting a high bar for interest rate increases and a tapering of asset purchases. However if the US economy bounces back sharply this year and moves closer to full employment by next year, the central bank is bound to consider an earlier removal of economic support than expected.

This would put it at odds with the ECB, which announced a “significant” increase in the pace of its bond-buying and predicted inflation would remain well below its target even in two years’ time.