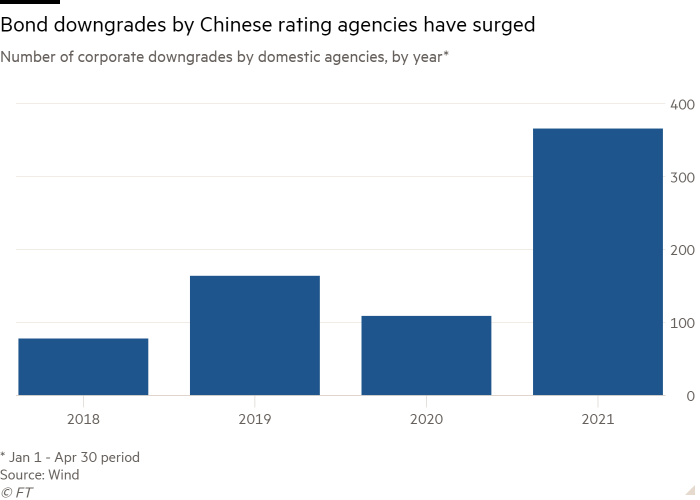

Domestic rating downgrades of corporate bonds in China have more than tripled this year, underlining Beijing’s efforts to reduce risk in the country’s $17tn credit market in the wake of several high-profile defaults.

International rating agencies and fund managers have long criticised China’s artificially high corporate credit ratings and low default rates, pointing to a lack of transparency and the assumption the government will bail out struggling companies.

But 366 bonds were downgraded in the first four months of 2021, compared with 109 in the same period a year ago, according to data from information provider Wind.

The increase followed a warning in November by Liu He, China’s vice-premier, that Beijing would have “zero tolerance” for corporate malfeasance in the aftermath of a series of defaults by state-owned companies.

Regulators have put pressure on debt underwriters, domestic rating agencies and auditors in an effort to encourage more timely disclosure of risks, analysts said.

Among the hundreds of downgrades this year were bonds issued by HNA, the formerly acquisitive conglomerate that has grappled with debt and liquidity problems for almost five years, and Tsinghua Unigroup, an important computer chip investor that has faced questions over bond repayments since 2018.

Charles Chang, greater China country lead at S&P Global Ratings in Hong Kong, said Chinese companies’ poor disclosure of risks was “starting to improve”.

“If that regulatory push is working, you should see an increase in timely action that flags underlying distress . . . that doesn’t mean there is an increase in distress, it just means that there is an increase in the indication of that distress,” Chang said.

S&P noted that more than 80 per cent of local ratings on non-financial corporate issuers in China were classed double A. Below that grade, Chinese groups cannot issue publicly traded debt.

Five domestic rating and auditing firms contacted by the Financial Times did not respond to requests for comment.

Chinese regulators have struggled for years to improve transparency in the country’s corporate debt market. Increasing scrutiny by regulators has become acute for debt-laden state-owned enterprises, analysts said.

The focus has sharpened since a bond default by state-backed Yongcheng Coal and Electricity in November sent shockwaves through China’s financial system.

Some of the defaults could also have been due to the economic damage wrought by the coronavirus pandemic, analysts said, despite China’s return to pre-pandemic levels of economic growth in the final quarter of 2020.

Xiaoxi Zhang, an analyst with Gavekal Dragonomics, said China’s leaders had singled out “hidden debt” as a priority this year, and were working to change market perceptions that many companies carried an “implicit guarantee” that the state would bail them out.

“The government wants to take advantage of the strong growth momentum of the post-Covid rebound to deal with structural problems,” she wrote in a research note.

“But it’s also because the current tightening of credit and withdrawal of supportive economic policies could cause broader financial stress if hidden debt is not handled well.”

S&P’s Chang, however, pointed out that default rates in China remained comparatively low. “China’s default rates would need to double or triple to reach the level that you see in the US, in Europe and emerging markets,” he said.