Four years ago, when Ant Group’s premier money market fund was racing to a peak of more than $260bn worth of assets under management, many of China’s state-owned banks and their regulators started to get agitated. In a series of calls and meetings with Jack Ma, Ant’s founder, bank executives and regulatory officials demanded that its Yu’E Bao fund be reined in.

“Yu’E Bao was pulling a lot of money from the banks,” says one person familiar with the discussions. “The banks were worried about the impact on liquidity and wanted Ant to take measures to minimise the impact. The conversations were pretty tense.”

In the end, Mr Ma had to back down and Yu’E Bao imposed caps on how much people could deposit. Between March and December of 2018, its funds under management fell by a third to $168bn and stood at $183bn last September.

The stand-off, which has sparked rampant speculation about Mr Ma’s whereabouts, could become a defining moment for the future of private business in Mr Xi’s China.

On December 24, China’s market regulator announced it was launching an antitrust probe into Alibaba and sent investigators to its headquarters in the eastern Chinese city of Hangzhou, Mr Ma’s hometown. The announcement came just two weeks after the party’s politburo said it would target monopoly businesses to prevent the “disorderly expansion of capital”.

The move on Alibaba also came two months after financial regulators dramatically cancelled Ant’s planned $37bn initial public offering, which would have been the world’s largest.

Taken together, the measures amount to an unprecedented squeeze on a business empire whose ubiquitous services are central to the functioning of China’s pioneering online economy. Ant says Alipay, its payment app, is regularly used by 700m people — half of China’s total population — and 80m merchants, processing payments worth Rmb118tn ($18.2tn) in the group’s last financial year.

Alibaba’s shares have fallen by almost 30 per cent since the regulatory showdown began in late October, putting a big dent in the net worth of Mr Ma, who has not been seen in public since then. Over the same period his fortune has declined from $62bn to $49bn, according to Bloomberg data. The Hurun China Rich List estimated that Mr Ma had been the country’s richest man as recently as October 20 but would now rank fourth, his top slot taken by a bottled water tycoon, Zhong Shanshan.

The results of the showdown will say a lot about the sort of economy that China is developing. If Ant and Alibaba are crippled by regulators — or its founder is personally targeted by investigators — it will go down as a landmark moment in the party’s fickle relationship with China’s private sector even though Mr Ma is, ironically, a party member himself.

Since Deng Xiaoping launched the “reform and opening” era 40 years ago, the party has become ever more dependent on private sector companies for economic growth, job creation and tax revenues. But the party’s fixation with control, especially since Mr Xi came to power almost a decade ago, also triggers periodic crackdowns on the sector and prominent entrepreneurs.

Yet there is another potential outcome that would indicate a less fraught relationship between the party-state and business. The investigations into Ant and Alibaba could lead to the sort of settlements that are not dissimilar to those pursued in the US and EU against large finance and technology groups. That would leave Mr Ma’s two flagship companies humbled but still formidable and highly profitable national champions. Even then, a strong political message would have been sent.

“Chinese internet magnates can still enjoy thriving businesses and enormous fortunes if they are able to convince the top leadership of their loyalty,” says Chen Long at Plenum, a Beijing-based consultancy. “The top leadership wants to ensure that neither Ma nor anyone else ever crosses the red line of trying to exert personal influence over government policies again — at least not publicly. The government will support them on the condition that they serve the national interest first.”

Fintech revolution

Mr Ma has not appeared in public since October 24, when he gave a high-profile speech critical of the same state-owned banks he clashed with over Yu’E Bao’s rapid growth, as well as regulators who he said often sacrifice innovation on the altar of stability. According to people involved in the listing, the speech angered Mr Xi, who made the final decision to halt the Ant IPO.

“To innovate without taking risks is to strangle innovation,” Mr Ma said. “There is no such thing as riskless innovation in the world. Very often, an attempt to minimise risk to zero is the biggest risk itself.”

He was speaking at the same forum where Wang Qishan, Mr Xi’s powerful vice-president and former anti-corruption tsar, had earlier emphasised the paramount importance of financial system stability. “Efforts should be made to prevent and lower financial risks . . . security always ranks first,” Mr Wang said. “While new financial technologies have improved efficiency and brought convenience, financial risks have been heightened.”

In an unprecedented public rebuke of Ant two months later, on December 26 China’s central bank criticised Ant for being too cavalier about financial risk and taking advantage of regulatory loopholes. But as frustrated as regulators are with Ant, they cannot ignore the beneficial effects of the financial revolution it has led in China.

“Ant Group,” People’s Bank of China vice-governor Pan Gongsheng admitted in his otherwise critical comments, “has played an innovative role in developing financial technology and improving the efficiency and inclusiveness of financial services”. The central bank, he added in a nod to jittery entrepreneurs, was also “unshakeable” in its commitment to “protect property rights and promote entrepreneurship”.

Mr Ma has long enjoyed support from officials in a range of State Council ministries, as well as the lead financial regulators, who appreciate the contributions of Ant, Alibaba and their rivals, all of whom have transformed China’s economy and made its online services sector a global leader. When his status as a party member was first confirmed only two years ago, it was in the context of an award he was receiving from the party’s Central Committee for “making China a leading player in the international ecommerce industry, internet finance and cloud computing”.

Alibaba and Ant’s ecommerce and online payment services were even more critical at the height of China’s successful battle to contain coronavirus, providing essential services to the hundreds of millions of people caught in draconian lockdowns.

“There are different lines of thought within the regulators,” Mr Chen says. “Until Jack Ma’s speech the pro-growth people had the upper hand. But Xi thought the speech was too much and a second [risk-averse] group took the lead. If his speech hadn’t happened, everything would have been fine.”

Disappearing acts are unusual for Mr Ma, who also missed the November finale of his African reality TV show — Africa’s Business Heroes. He routinely gives flamboyant musical performances at Alibaba events and hobnobs with heads of state and government leaders.

As China’s most successful private entrepreneur, Mr Ma enjoys unique status in China — and overseas. His fluent English has made him a huge celebrity on the international conference circuit, with a star quality unmatched by any of his private or state-sector peers.

When Mr Xi hosted the G20 leaders summit in Hangzhou in 2016, some of his guests also visited Mr Ma — something that irked the Chinese president, according to one diplomat involved and other people familiar with the matter. Mr Ma’s VIP callers included Indonesian president Joko Widodo, Canadian prime minister Justin Trudeau and the then Italian premier, Matteo Renzi. Foreign leaders were offered limited time slots and the Chinese foreign ministry was mostly cut out of the process.

Over the past week rumours about Mr Ma’s whereabouts have abounded on China’s carefully monitored social media channels, while domestic media outlets have received strict instructions from censors about the stories they can and cannot run on Ant and Alibaba’s regulatory troubles.

Many of Mr Ma’s friends and colleagues strongly dispute suggestions that he is personally in any sort of legal jeopardy, let alone on the run. “He is in China and not travelling because of Covid, not anything else. He’s lying low,” says one friend of Mr Ma.

Another friend who communicates with Mr Ma regularly adds: “Everyone is asking me if he’s in danger, but he’s doing fine. He responds [to messages and calls] quickly and seems like he’s in good spirits. Discussions with regulators are still very much in process so he just has to stay quiet until they are resolved.”

Leadership missteps

Friends add that while Mr Ma may now regret the consequences of his October 24 speech, he meant what he said and still believes passionately in what he sees as Ant’s mission to transform the provision of financial services in the world’s second-largest economy.

Yu’E Bao, which translates as “account balance treasure”, was started in 2013 and allowed anyone in China, from restaurant staff to the urban yuppies they serve, to deposit as little as Rmb1 ($0.15) in a money-market fund and earn more interest than they could in a Chinese savings deposit account. Just four years later it became the world’s largest money market fund, surpassing JPMorgan’s US government money market fund.

The fund’s success was a dramatic demonstration of Ant’s potential. But it was also a threat to one of China’s most powerful vested interest groups — state banks and the officials who regulate them. The central bank was also concerned. In its annual financial stability report published in late 2018, the PBoC said it would “strengthen regulation of systematically important money market funds”, without mentioning Yu’E Bao by name.

“When a taxi driver can deposit one renminbi in a money-market fund and get interest, that’s a big breakthrough,” says a former Alibaba executive. “Jack feels what Ant is doing is good for society.”

Mr Ma’s companies have rebounded strongly from regulatory disputes before, although Ant and Alibaba never faced scrutiny as intense as they now do. Ant’s run-in with banks and regulators over Yu’E Bao, for example, did little to hinder its overall business or influence.

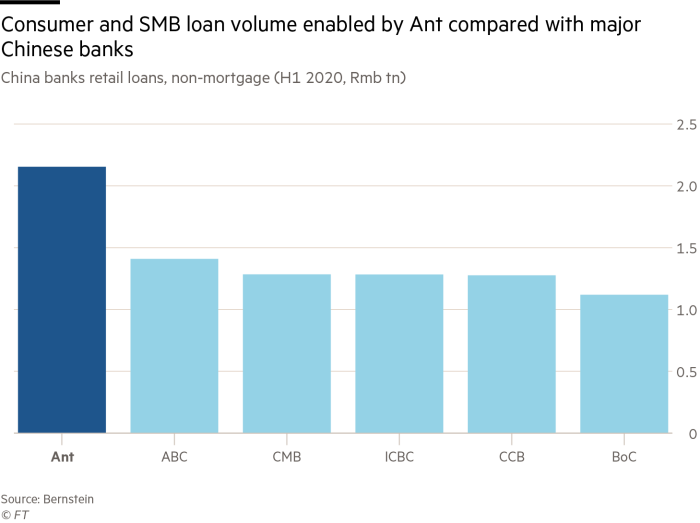

Ant’s credit business grew so large that it now facilitates about one-tenth of all of China’s non-mortgage consumer loans.

The group also aligned its interests with those of powerful investors. Ant’s first fundraising in 2015 brought in a slew of well-connected shareholders, all of whom were set to be rewarded handsomely in the IPO. The Chinese government’s social security fund and a group of state-owned insurers held stakes in Ant valued at, respectively, Rmb48bn and Rmb45bn at the IPO price.

Shares belonging to an investment vehicle put together by Boyu Capital, whose executives have included the grandson of former Chinese president Jiang Zemin, were valued at Rmb15bn. Even China Central Television, the country’s state broadcaster, held Ant shares worth Rmb3bn.

“Financial regulators have been very concerned about Ant’s growing power and ability to push back against any attempts to bring it under control,” says one Chinese government adviser. “Previous attempts to bring Ant under more control were not really working because it was so big and so powerful. There is now clearly a very dramatic shift.”

Bill Deng, a former Ant executive and co-founder of XTransfer, a cross-border payments platform, says Mr Ma may have become too confident.

“For a long time, regulators let Ant expand and I think [management] became a bit too complacent,” he says. “If there are hundreds of people praising you, you can get overly optimistic. Financial deleveraging policies have been a trend for several years now and the government is extremely careful when it comes to finance.”

Healthy growth

The cancellation of Ant’s IPO triggered a cascade of official and state media criticism of the fintech group. Regulators have also made clear they want the group to shift many of its businesses — including payments, lending, insurance and wealth management — into a new, more tightly regulated holding vehicle. This will increase Ant’s capital requirements and lower its valuation.

Authorities see the holding company model as a way to rein in large financial conglomerates while increasing their transparency. They also want Ant to share its vast trove of consumer data with the central bank — something it has refused to do before.

Having to wait for a smaller return than they almost locked in a few months ago will be disappointing for Ant’s investors, but there are worse alternatives. “The Chinese government does not want to kill Ant, but to make sure it grows in a healthy way,” says Mr Deng. “Ant can surpass its current obstacles. If they have patience, they will be able to rise again.”

As for the antitrust investigation into Alibaba, a manageable outcome for the group would include an end to exclusivity arrangements that restrict merchants from selling on rival platforms. Alibaba could also potentially face a large fine — the maximum allowed would be 10 per cent of its previous year’s revenues — if it is deemed to have violated China’s anti-monopoly law.

“Debates about exclusivity have been going on for years, it’s a competitive market,” says the former Alibaba executive. “I don’t think Alibaba is going to get broken up. It’s just that the methods by which they fight for the market are going to be more regulated.”